Columns

Songs of hate

Singers often overlook controversial subject matters, not least caste and gender discrimination.

Mitra Pariyar

A group of Dalit activists from the Caste Watch Network (CWN), with which I am associated, visited Pokhara on the weekend to discuss an improvised folk duet that was broadcast on YouTube a while ago. We objected to the song due to its casteist lyrics.

I often watch or listen to improvised folk duets freely available on YouTube channels. Most of these songs are about love and romance, and some spread positive social messages too. But there are folk presentations that directly or overtly preach hatred against the oppressed groups, including the ‘low caste’ and women.

‘A curse of the Sarki’

This is a serious issue because popular music can have a powerful influence on society, including the younger generation. Negative representations of the marginalised castes and communities can further exacerbate and perpetuate domination.

I recently discovered a line in a folk duet by a fairly popular singer from Pokhara that directly offended the Dalit community, particularly the Sarki. Spontaneously responding to the male contender, the singer said, “A bull won’t die just because a Sarki brother has cursed it!”

This is a casteist proverb still used in rural hinterlands, which insults Dalits, mainly the Sarki. The Sarkis have long been stigmatised for their traditional trade–tannery. They are also humiliated and excluded for their traditional culture of consuming beef, including that of the dead cattle (which they are still forced to remove in many parts of the country, especially in the far-western and Karnali regions).

Surprisingly, nobody had raised a voice against this offensive lyric of the aforementioned song even though it had been uploaded to YouTube several months earlier. Downloading just the insulting bit of the music, I posted it to my Facebook, expressing my utter disgust and seeking justice for the offended. If not resolved properly, we would take the singer and the owner of the YouTube channel to court.

Actions taken

A caste association of the Sarki community from Pokhara noticed the post and summoned the singer to the District Administration Office in Kaski. The angry men and women threatened to take legal action against her, but she was pardoned after she apologised in writing and pledged to take the video down and never repeat such mistakes.

After the video was taken down from the YouTube channel, I was asked to remove the extracted clip from my Facebook wall. Over 10,000 people had already watched the clip, and many expressed disgust and anger at the singer.

We wanted to delete the Facebook post after personally meeting both the singer and the owner of the YouTube channel and warning them about the seriousness of the matter. Our goal was to use this case as a strong warning to other performers as well.

The singer apologised to us, too, and promised to be vigilant about casteist expressions in her musical performances in the future. The channel owner, himself a singer from a Dalit community, didn’t show up. But over the phone, we advised him to be careful over the phone before taking down the offensive clip from Facebook. The notifications about the whole affair on my Facebook pages did, hopefully, spread the intended message about avoiding caste hate in musical shows.

Folk culture and casteism

Gone are the days when the townspeople looked down upon folk music as the sound of the rustic–of the backward class. In towns, people used to enjoy Hindi movie songs and ghazals, as well as the so-called modern Nepali songs–Narayan Gopal is a legend of this genre–which often contained literary expressions and deeper meanings. People still enjoy Hindi music, but the folk music from the village has trumped all other Nepali music genres.

Now, “dohori” restaurants have become popular in Kathmandu and other towns. They feature live folk singing and dancing, and traditional costumes and artefacts. Once popular ghazal restaurants have almost gone extinct.

Thus, people get a cultural feel of their home villages in towns. Aspiring country singers hailing from the rural areas can both make a living and hone their talents in these musical venues in Thamel, New Bus Park and some other parts of the capital city.

Folk singers, musicians and dancers can make some money performing live on stage. These performances are a regular part of many festivals held nationwide. Some lucky singers even get a chance to travel abroad and earn a quick buck by performing to audiences in diaspora communities, including those in the United States of America, the United Kingdom, Australia, Gulf countries, and Malaysia.

More importantly, thanks to the popular use of smartphones and social media apps in Nepal, many people, including singers and musicians, have opened their own YouTube channels. They regularly record improvised folk duets in the studios, post them to their channels, and promote them on other platforms such as Facebook and TikTok (yes, TikTok is still running through VPNs despite the government ban). Some singers have been able to earn substantial amounts from their YouTube posts.

Since competition is getting tougher by the day, singers and channel owners are under increasing pressure to give better presentations and to find new and unique ways of attracting the audience. In so doing, they sometimes forget or overlook–or deliberately use–sensitive and controversial subject matters, not least caste and gender discrimination.

Many popular folk singers and composers come from the Dalit community. Raju Pariyar from Lamjung District is popularly considered the ‘king of folk music’. Prakash Saput from Baglung is another highly talented Dalit singer whose many songs have gone viral on YouTube.

Sadly, even the best talents of the folk music industry tend to be publicly humiliated or insulted based on their castes. Contenders from the Magar or Gurung or ‘upper castes’ dominate the contenders from Dalit communities during dohori performances.

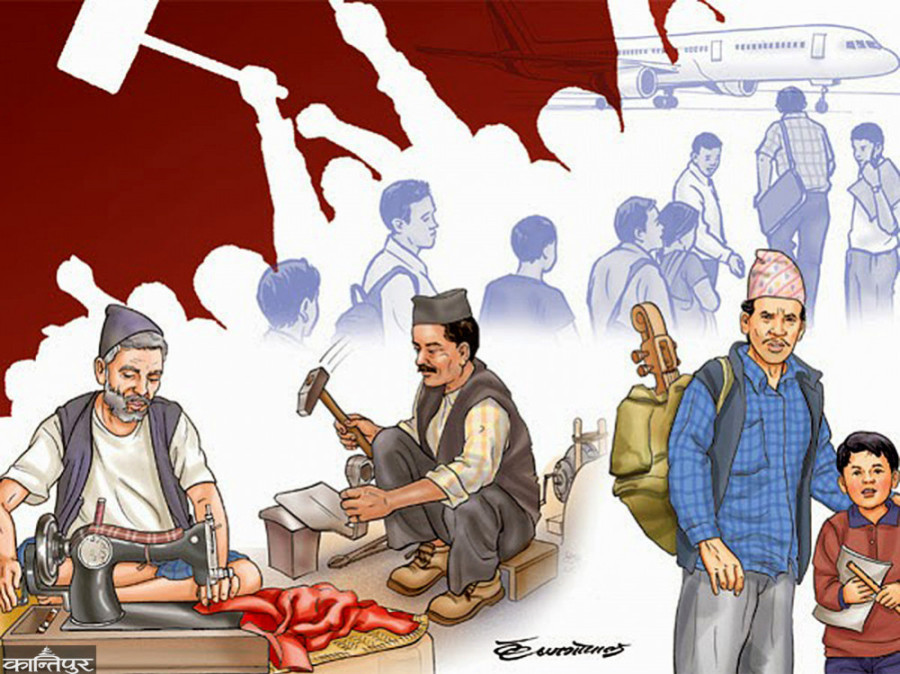

In numerous duets, for example, female singers from the ‘dominant castes’ have asked Raju Pariyar to make their wedding dresses or to play his drum or pipe during their weddings. As stated before, Pariyar, despite being a superstar of the folk music industry, is reduced to a tailor, a drummer or a piper because of his ancestral and highly stigmatised occupations.

Sometimes Dalit artists themselves provoke caste hate, unwittingly perhaps. Prakash Saput’s folk album ‘Damai Maharaj’ is a solid example of this. Saput probably wanted to challenge caste hate through this beautiful music, but the words, and the associated drama, are such that they end up reifying and reaffirming Brahmanic views of caste instead. Through the song, Prakash announces that Hindu scriptures never preach or promote caste discrimination. There are scenes of revering the Brahmin pundit or purohit and offering him tuladan (gold, silver and/or grains equal to his body weight).

We should avoid promoting casteist views in all sectors of art and culture. Folk songs deserve greater attention as they dominate the music industry and influence social psychology. Dalit or not, all artists must be held accountable so that they aren’t able to promote casteist views in society. Their talents must instead be used effectively to spread anti-caste beliefs and values.

8.79°C Kathmandu

8.79°C Kathmandu