Columns

Nuwakot Dalits: A grim story

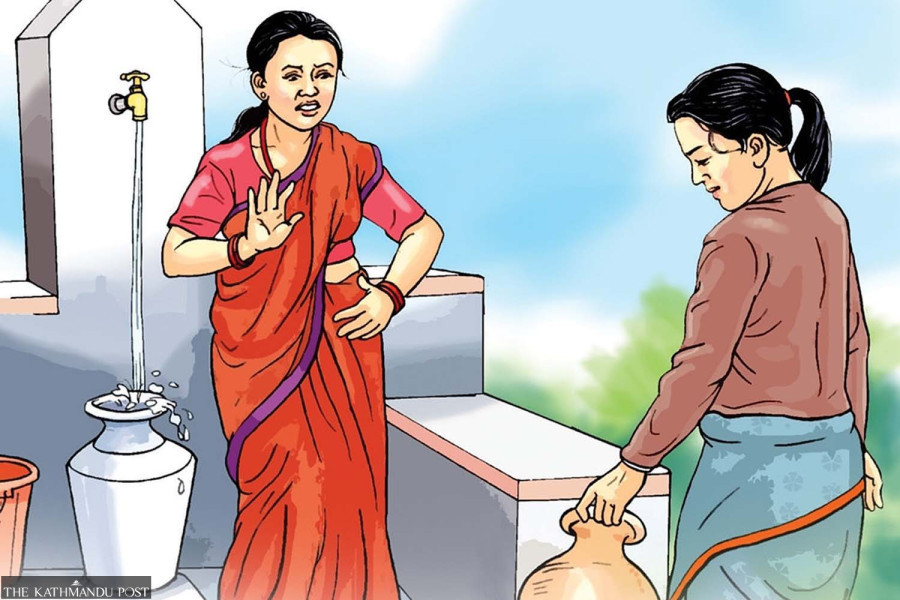

Water is considered a superconductor of ‘caste pollution’ in our Hindu-dominated society.

Mitra Pariyar

It was the warm and sunny morning of March 9, and our team (Dalit activists with the Caste Watch Network and a journalist) gathered at the Machhapokhari junction in Kathmandu. An electric van took us across Balaju Bypass and Tokha before we climbed the hill of Shivapuri, dotted with red rhododendrons. As we descended towards the other side of the hill, our eyes, lungs and ears sang joyfully. The scenery was great, and we had left the hustle and bustle of the capital city behind.

We were also increasingly conscious that while the physical environment had become much cleaner, the social environment was getting increasingly filthy. Caste bites harder in rural areas. An unbelievable incident associated with this caste pollution—as it were—had caused us to make this two-and-a-half-day trip to the village of Chainpur in ward number 12 of the Bidur Municipality, Nuwakot district.

Water: Superconductor of caste

It is common knowledge that access to drinking water has been a principal source of conflict between nations, people, ethnic groups, cities, villages, settlements, neighbourhoods and even households. A cruel principle and practice of many Hindu communities in South Asia and beyond has been to deny the Shudra access to clean drinking water.

In Nepal, the very definition of “low caste”—published in the 1854 Civil Code, the nation’s first written constitution—is “someone whose water cannot be used by others”—pani nachalne jat. In religious and cultural terms, the same principle is strongly held in society today, even though the formal laws have changed over time.

Water is considered a superconductor of “caste pollution” in our Hindu-dominated society. Caste pollution through contact with low castes is purified, for example, by sprinkling water that has been sanctified by dipping a piece of gold in it. Not everyone would practise this now, of course, particularly in towns, but the traditional belief is still strong in society.

It is commonly held that upper castes’ lineage deities and other gods will get angry if the Shudra touches their water. Many homes in Kathmandu and other towns refuse to rent their rooms or flats to the low castes because they fear the Shudra’s touch contaminating their water, mainly the water used for daily worship.

Across the swathes of the countryside, sources of water have been the principal sites of caste domination and humiliation. Even today, we hear stories of Dalits being openly excluded and humiliated, if not physically assaulted, when they attempt to share the wells and taps with other castes. Dalits are told to either use the wells and taps after other castes have used them or to drink the dirty water from these sources.

The Nuwakot story

The things happening in the Chainpur village of the Nuwakot district are quite extraordinary, something not seen or heard about in some of the most casteist societies of the far western and Karnali regions. This village on a dry slope suffers from an acute shortage of clean drinking water, and the municipality has done little to resolve the crisis.

A little spring in the field of a Damai family has caused much contention in the community. It has potentially risked the life and property of the family there. This is what we had come to observe and report that day and, if possible, to resolve the dispute. We had been invited to the site by relatives and friends of the victims.

The Dalit family has collected and used fresh, clean spring water for generations. A Chhetri man wants to use it as well, but not share it with the Dalit family! The Dalits are happy to construct a small reservoir and share water with the Chhetri family, but the Chhetri man does not accept this proposal. He believes using water from the same source would be ritually polluting, thus potentially offending his deities.

The upper-caste man has been using every tactic, including money and muscle, to harass the Dalit family so that he will be able to gain full control of the spring. He has tried to beat the Dalit man into submission. He has showered rocks on the Dalit home. Emboldened by his own nephew as the ward chairman, he has also filed a case in the district court, accusing the Dalits of denying his use of the spring. He has concocted the myth that his family has used the water for decades.

The victim family is living in grave danger, but they are not going to give up easily. They have sought the help of the ward office, the local police and the local judicial committee to resolve the crisis. The Dalit couple is happy to share water with the Chhetri family, but they cannot afford to let the bully fully appropriate it.

Our efforts

Typically, local Dalit households have been unable to come together to seek justice for the victims. Local political economy means that the relatives and friends of the suffering Dalits are unable to speak up. After all, dominant Chhetris are often the sources of their livelihoods.

The place is less than 80 km away from Kathmandu and overlooks the growing town of Bidur—yet the traditional patron-client system is still strong here. The tailors—who cannot enter homes and who must wash their own dishes after eating and drinking there—visit upper-caste clients in their homes to make new dresses or to mend the old ones. They are paid little, often in the form of grains and old clothes, for their services. In a word, caste discrimination is strong here, and nobody seems bothered.

We visited the spring, interviewed the victims and organised a small gathering on a common platform. The alleged victimiser did not turn up to discuss the matter. The victims were quite vociferous about their plight and adamant that they wouldn’t relinquish their right to use the natural spring on their own property, no matter what. They directly accused the ward chairman of not protecting the victims and throwing his weight behind his abusive uncle instead.

The gathering also involved the district representatives of the Dalit wings of the major parties—the Nepali Congress, the CPN-UML and the Maoist Centre. They did offer some lip service but clearly were not able to defend the rights of the victims. The incident was tricky for them, too, as the offender belonged to the Congress party and was the uncle of the ward chairman of the Maoist party. Partisan interests often render Dalit activists ineffective, which has also been the case in this village.

As activists, we did our best to convince the gathering to protect the lives and properties of the Dalit family and ensure their right to use the water originating on their own property. We posted a video clip of the whole affair, including the views of the victims, chairman and Dalit representatives on the Facebook page of the Ujyaalo Network channel which has thus far been watched by over 1.3 million.

My hope is that with the video going viral, the suffering Dalits will finally get justice. If anything, the video will discourage the perpetrators and encourage those, both Dalits and non-Dalits, on the side of justice. Hopefully, this will also influence the district judge’s decision, who will rule on the case filed by the aggressor himself.

8.79°C Kathmandu

8.79°C Kathmandu