Columns

Mind your businesses

An open letter to FNCCI president Chandra Prasad Dhakal calling for internal reforms.

Bishal Thapa

Dear Mr Dhakal,

Congratulations on your appointment as president of the Federation of Nepalese Chambers of Commerce and Industry (FNCCI), though it has been a few months already. You helm the largest umbrella organisation of businesses in Nepal, representing approximately 1,000 private enterprises across the country.

My aim in this letter, though unsolicited, is to encourage you, and other business leaders, to introspect on the role of private enterprises in Nepal, and perhaps, recognise what is now at stake.

A lot is at stake

Several years ago, I had written a similar open letter to the then FNCCI president Bhawani Rana calling on her to push for internal reforms and structural changes within Nepali business. In half a decade or so since then, Nepal’s vulnerabilities, instability and uncertainties have deepened and become more visible.

The global pandemic swept through Nepal stressing many of our already weak social services and causing severe economic distress. Nepal’s current account deficit, which describes how much more we import over export, and a key metric to watch given our dependence on imports, reached a record high of 12.8 percent of the gross domestic product (GDP) in the fiscal year 2022, the April 2023 development report from the World Bank indicates.

Foreign exchange reserves increased to approximately $10.5 billion in the six months between July 2022 and January 2023, enough to cover approximately 9.4 months of imports. That’s well over the government’s minimum threshold to have enough foreign reserves to cover seven months of imports. But that cushion of foreign exchange reserves has been built on import restrictions and remittance income.

The crisis in foreign exchange reserves appears to have faded, but the process of rebuilding them through increased remittance income and import restrictions exhibited our economic vulnerabilities. These vulnerabilities continue to haunt us. Several import restrictions are still in place, and Nepali men and women are again tearfully departing in droves for the only meaningful option they have—working abroad.

Foreign exchange reserves are only one of the many aspects of the economy that are worrisome. The growing public debt burden, for example, is another. The government still has enough borrowing space for now. But with public debt growing rapidly and now at approximately 38.3 percent of GDP, the concern is that poor borrowing decisions for unproductive infrastructure assets has eroded the available space for investment in truly productive projects.

Signs of distress are visible everywhere. The increase in the levels of non-performing loans in the banks, which have doubled to 2.6 percent over the last year, wasn’t only because the central bank removed the refinancing facility. It is also an indicator of economic slowdown, poor lending practices and even poorer borrowing habits finally beginning to catch up. Government tax revenues are similarly down, in part because imports have fallen, and because overall economic activity is subdued.

You, and other business leaders, probably know these numbers and understand their implications better than anyone else. But the real story of Nepal isn’t in the numbers. It is in the broader climate of despair and disillusionment. A foreboding sense of crisis now prevails.

Time to act

Nepali businesses, particularly large businesses within the formal economy, have evaded their responsibilities for internal reforms. They have failed to keep pace with the broader political and social transition of Nepal.

This transition has been far-reaching. A new constitution with a secular federal republic has been established. Greater equality and fundamental rights in access to health, education and fairness have been granted. Much more work remains, no doubt, but at least the basis for political and social changes has been laid.

What transformations have Nepali businesses delivered?

Other than a realignment in influence and political access, and some space for upstarts from outside of Kathmandu, Nepali businesses have largely remained unchanged. In corporate governance, transparency, ownership, gender and ethnic inclusivity, environmental stewardship, or social consciousness, large businesses within the formal economy have maintained the status quo even as the rest of Nepal has changed.

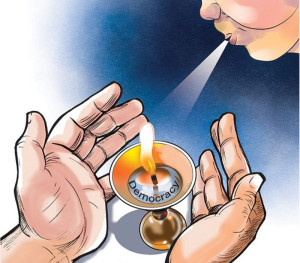

This status quo is unsustainable. It is now also necessary for the self-preservation of the private sector. Far in the distant horizon, the public’s feeling of despair and disillusionment are adding up, fermenting a new set of forces, or realigning old ones. The tempest is building. When that tempest spills over and rages, if it spills over and rages, a reordering of businesses will be the primary target.

The monarchy has been abolished. The Hindu state has been replaced with a secular one. Businesses are the only remaining target that could represent an impediment to Nepal’s progress.

You and other business leaders must act to identify and implement internal reforms. There are many things you could do. Let me suggest three.

First, expand your supply chain networks. Nepal’s economic transformation can only commence if large businesses integrate a wider cross-section of the economy within their supply chain network. This would allow larger sections of the economy to participate, be invested, share in, and benefit from the growth of the formal economy. It would accelerate overall growth and make it broad-based. Large businesses should seek to double, triple or quadruple the diversity of their supply chain partners, with at least most of the firm’s costs coming from inputs received from non-related third-party sources representing external supply chain networks.

Second, formalise your supply chain network arrangements. Nepal’s broader economic environment, the ease of doing business, for instance, can only be enhanced if large enterprises formalise the supply chain network arrangements. Documented agreements that codify the arrangement, terms, conditions and other covenants not only make it easier to enforce those agreements, but also help smaller firms that feed off the larger ones to gain certainty, secure investments and credit.

These will, in turn, help raise the demand for regulatory improvements. It is hard to push for better rules and regulations if most business arrangements remain informal between friends, family and relatives. Formalised supply chain arrangements will enhance, modernise and grow the economy.

Third, finance your supply chain network partners. Most Nepali businesses are small and medium enterprises that survive under the shadow of large firms. They benefit in one way or another from the supply chain arrangements with large enterprises. Small and medium enterprises have difficulty in accessing investments and lack the collateral to raise capital.

This is where large businesses can play a transformative role. They can emerge as the implicit investor to these smaller enterprises. Formalised supply agreements can be securitised and could be structured to serve as collateral. This would help smaller enterprises overcome their need for collateral, expand credit, foster investment, create stronger interdependencies and reinforce the value of the expanded supply network.

There is a lot more that Nepali businesses can do, and must do, to evolve and keep pace with the changes in Nepal. Whether Nepali businesses emerge as the last hope for or the final impediment to Nepal’s prosperity and development now depends entirely on what you and other business leaders choose to do.

4.12°C Kathmandu

4.12°C Kathmandu