Columns

Geopolitical shifts in the Indo-Pacific

Beijing and the US seem to be rethinking their positions, which could open avenues for developing economies.

Anurag Acharya

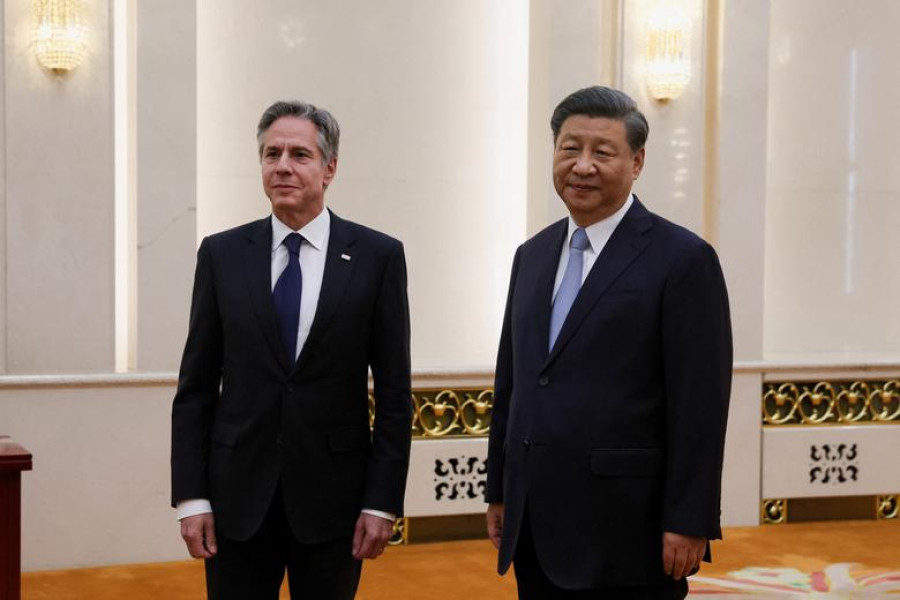

Less than 48 hours before Indian Prime Minister Narendra Modi landed in Washington, DC this week, US Secretary of State Antony Blinken held a one-to-one meeting with Chinese President Xi Jinping. This was the first high-level US delegation to Beijing since the Trump administration strained ties with Washington over five years ago. A number of immediate factors have contributed to the spiralling of the relations between the two powers, but they all boil down to the fact that Beijing wants to expand its global footprint, and that will come at the expense of the US conceding the influence it already wields across different regions. Nowhere is this competition more visible than in Asia, which has become a geopolitical hotspot.

Confronting reality

Over the past decade, China has exhibited increased economic and military prowess, signalling greater confidence to engage across global fora. Beijing’s continued support for regimes in Iran and North Korea—which have taken hostile posturing against the US and other European countries—has consistently come under criticism from Washington. China’s aggressive economic diplomacy through the Belt and Road Initiative (BRI) and military diplomacy in the Indo-Pacific region also alarmed the US.

Meanwhile, China has been condemning the presence of the US and its interference in the East and South China Seas. The region includes the contentious Taiwan Strait and several islands that China claims as its own, but countries like South Korea and Japan challenge it. Similarly, Washington’s strategic partnership with India has also not gone well in Beijing, as it directly challenges China’s ambitions in South Asia. Increased hostilities between India and China over the past years can also be attributed to what Beijing views as New Delhi ganging up with the US and Japan through their Indo-Pacific strategy.

Two global powers trying to out-wit one another has had a perilous effect in this part of the world. It has pushed China into increased hostility with its neighbours like India, Japan and South Korea. It has also dragged smaller aid-dependent economies into a difficult geopolitical quagmire, often destabilising their domestic politics. Countries like Sri Lanka, Nepal and Bangladesh have often found themselves struggling to balance off competing interests, as the geopolitical rivalry has fed into domestic political rivalries.

Therefore, Blinken’s visit to Beijing—timed aptly before Modi landed in Washington—will have great significance in restoring normalcy in the region, which has remained volatile in the past few years. His remarks to journalists immediately after meeting President Xi were clear and reflective of Washington’s shifting position. Blinken began by stating the importance of “responsibly managing the relationship” between the US and China and how that serves the interests of both countries and the World. He also shared how both sides had agreed not to let their mutual differences and competition lead to instability in the region, emphasising regular communication at the highest levels to achieve that.

A de-escalation of tensions between the two countries could stop both sides from manoeuvring against the status quo in the disputed international waters of the East and South China Seas. It may also lead to Beijing refraining from unnecessary provocations against India, which has established itself as an important US ally. Of course, there is always a danger of reading too much into these early developments, but there is a reason to be hopeful about two superpowers shifting their geopolitical positions.

Burden of Ukraine war

It may be hard to imagine that a war being fought in a distant land between Russia and Ukraine, two former Soviet republics, could become an essential factor in restoring stability in the Indo-Pacific. But the analysis is not as far-fetched. Russia’s reckless and irresponsible aggression against Ukraine has entered its 16th month, leading to over 60,000 deaths and 17 million displaced. The scale of destruction is huge and could be estimated at over $400 billion.

The economic impacts of this war, in a post-pandemic world, will be catastrophic not only for Europe but also the entire world. It will disrupt global markets and supply chains, but most importantly, it will limit the capacity of Ukraine’s allies, like the US, United Kingdom and other EU countries, to focus beyond the region. Even China will feel the impact of this war, as its important market will stagnate for the next few years. As an important Russian ally, Beijing will also be forced to support Russia when it recovers from the mindless war it has waged.

There are no winners in a war, at least not in a 21st-century world driven by fragile and interconnected markets that function on the predictable politics and economic decisions of governments. As two of the leading global powers, it is expected that the US and China would have come to a sobering realisation that continued escalation in the Indo-Pacific will add to the uncertainty and distract both countries from focusing on Europe’s economic and humanitarian disaster. The visit by the EU delegation to Beijing last month, and Blinken’s reiteration of China’s role in ending the war in Ukraine this week, strongly point to the possibility of a de-escalation in the Indo-Pacific.

Therefore, as Modi wraps up his visit to the US in the coming days, it is not too difficult to assume that Washington’s bottom line on China and the Indo-Pacific strategy may have been recalibrated already. The visiting prime minister should have no reason to be unhappy over what that means for his country. As for the rest of South Asia, which is still a footnote to that conversation, we can only be hopeful about the development avenues that will follow a period of stability.

8.54°C Kathmandu

8.54°C Kathmandu