Columns

A Nepali rebel in Tibet

Little is known of KI Singh’s life in Tibet, where he escaped after a failed coup attempt.

Amish Raj Mulmi

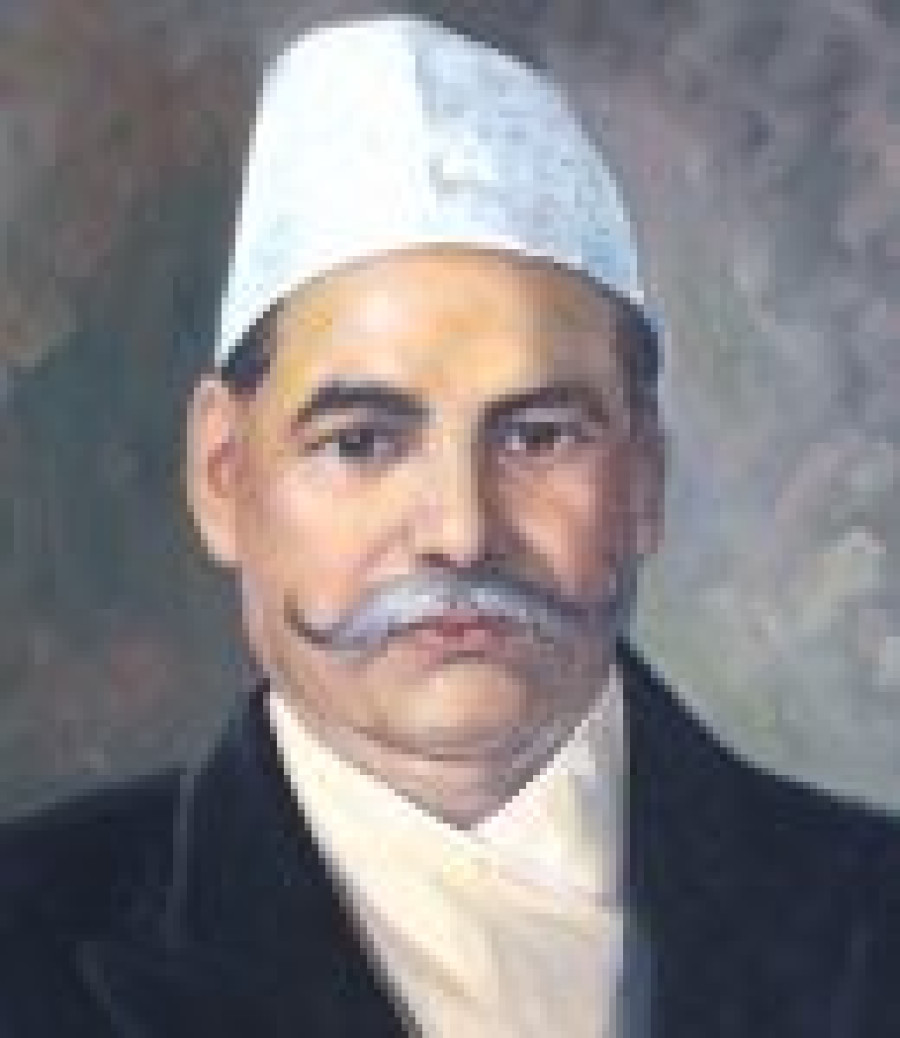

One of the most colourful of characters in Nepali politics was Kunwar Inderjit Singh, otherwise known as Dr KI Singh (1905-82). The "Robin Hood of the Himalayas" had fought for Indian revolutionary Subhas Chandra Bose’s Indian National Army, practised homoeopathy (hence the title "doctor"), led an armed assault on Rana forces in Bhairahawa during the 1950 revolution, redistributed land to peasants; and when dissatisfied with the 1950 agreement, raised his banners against the government. Singh was arrested in 1951 and imprisoned in Kathmandu. In January 1952, he broke out of prison and attempted a coup, failing which he and 37 of his followers left for Tibet.

In 1955, after China and Nepal established diplomatic relations, Singh was pardoned by King Mahendra and returned to Nepal. Two years later, in July 1957, he was appointed prime minister, a tenure that was to last four months. His subsequent political career was a flip-flop between supporting the Panchayat regime or the multi-party system.

Little is known of Singh’s life in Tibet, except that he had supposedly asked China to help him overthrow his government. Archival documents, however, reveal Nepal’s persistent efforts to extradite him, which were resisted on grounds of Chinese policies. Singh had certainly tried to make himself useful to Chinese authorities, but the latter weren’t too impressed, and in fact, were unsure about what to do with someone who had attempted a coup against a government they had no formal ties with at the time.

Singh in Tibet

KI Singh arrived in Tibet in January 1952, crossing over from Rasuwagadhi. The Nepali representative in Lhasa prepared an assessment for Kathmandu, which was passed on to friendly governments such as India and the United States since the Nepal government wished such governments to be "apprised of developments in Lhasa". These reports, prepared by the US Embassy in Delhi for the State Department and other missions, indicated a convergence between the interests of the other powers and Nepal at a time when the Chinese People’s Liberation Army had recently entered Tibet.

In April 1952, the Nepali representative was asked by four members of the Kashag, or the Tibetan governing council, whether Singh’s extradition request had come from Kathmandu or from the representative himself. "Subba Youdha Gambhir told them he had made the request…on receipt of instructions to that effect from the Government of Nepal." The Kashag members told him they would consult on the decision and revert, although he was told informally Tibet would assist Nepal according to the terms of the 1856 treaty between the two states. The Indian representative, Sumul Sinha, also thought the same, and hoped China too would not object to Singh’s extradition.

Meanwhile, reports from Shigatse suggested Singh had been drawing maps of Nepal showing the various passes "leading from Nepal into Tibet". In Sekar Dzong, a dispute arose between Singh’s party and a Tibetan over a rifle sold by one of his followers. Both parties were to be punished by flogging, and Singh appealed to the authorities to punish another follower of his for "not carrying out his orders on the way". Reports also suggested "the Chinese are not allowing Dr KI Singh to move about freely", and that Singh and his party were being made to wear "the same kind of dress as the Chinese themselves wear". Singh had also requested the Chinese to send him to Beijing to discuss various matters with Mao which "he could not disclose to so many different grades of Chinese officers". He’d also told them "officers from many countries including Americans now in Nepal are busy completing preparations to fight with China, and that the Chinese also should not remain inactive any longer but should be prepared for any eventuality". A June 1952 report from the Indian mission confirmed Singh had "emphasised the urgency of liberating Nepal".

Singh was escorted to Lhasa by Chinese authorities on May 26, 1952, and was put up at the home of the noted Pangdatsang family. "The Chinese do not allow these Nepalese to move freely, and have appointed a strong guard over them." Singh and his retinue were warned on "pain of punishment" not to speak with anyone, and were only provided rations and clothes.

The Nepali representative immediately went to the Kashag to emphasise on Singh’s extradition, which was once again deferred. In June 1952, the representative was told that since Singh had sought asylum in Tibet, he could not be extradited according to Chinese laws, but Chinese authorities in Tibet had enquired with Beijing about Nepal’s demands. By August, the Nepali mission was running out of patience. "It seemed to our Representative that KI Singh’s case was being kept secret, for the Kazis did not wish to meet and talk about this matter." There were widespread rumours that Singh had already been taken to Beijing (he was first taken to Chengdu, and was taken to the Chinese capital only in May 1953). By September, the Nepalis were told in no uncertain terms by the Tibetans that the Chinese would not go against their policy of non-extradition.

Return to Nepal

Because China and Nepal were yet to establish diplomatic relations, and the Nepalis were communicating directly with the Tibetans about Singh’s extradition, China too seemed to be at a loss as to what to do with him. However, the Chinese did not regard him as a revolutionary, but more as a political fugitive. "The Chinese rarely, if ever, publicised his arrival or used him in politically motivated ways… There also does not seem to be any evidence that they contemplated at any point benefiting from his presence in fomenting Communist activity in Nepal." Going by reports about his confinement in Lhasa and thereafter, one can assume Singh’s presence was discomfiting to the Chinese too. Zhou Enlai told him after the 1954 India-China agreement that Beijing "would never send even one soldier" to Nepal, and once the 1955 Nepal-China agreement was concluded, Singh was no longer useful.

By the end of August, Singh and his followers arrived at Rasuwagadhi, awaiting the royal pardon. A few days later, "[w]ith a band playing, Singh proceeded through the streets of Kathmandu in September, half the population having turned out to see him". At a public gathering, Singh praised India to the surprise of many, not least Indian Prime Minister Jawaharlal Nehru, who later called him "not a Communist–just a freebooter".

Despite such a colourful life, one cannot yet say with conviction whether Singh was a revolutionary or an opportunist. What is certain is that Singh was perhaps one of the earliest Nepali politicians whose positions shifted wherever the winds took him. Many today would be inspired by his antics.

17.56°C Kathmandu

17.56°C Kathmandu