Columns

Vigilance against black fungus

This is an opportunistic infection mainly affecting immunocompromised people.

Balmukunda Regmi

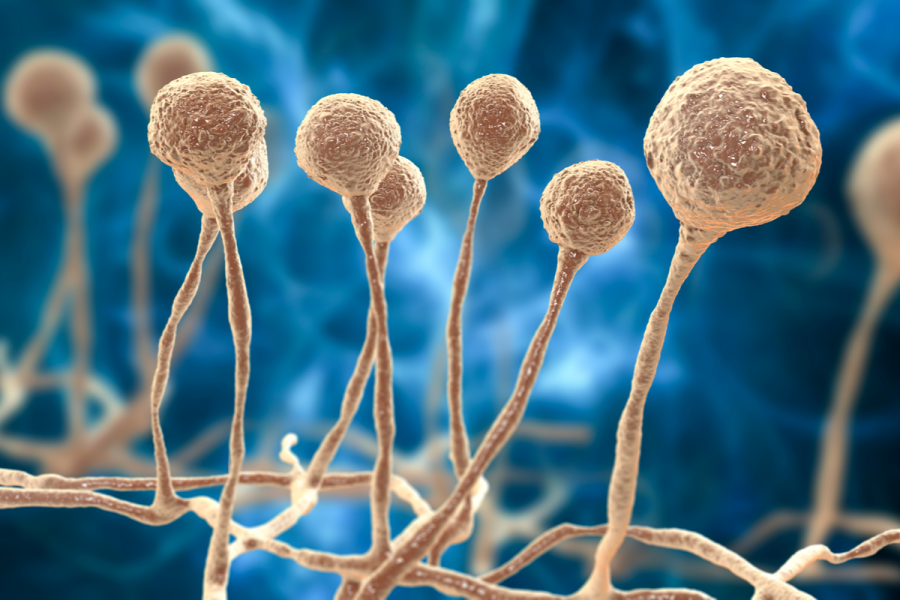

At a time when we are trying to contain the highly contagious coronavirus, a new threat, an outbreak of infection known as mucormycosis, popularly called black fungus, has emerged. It is caused by a group of transparent moulds called mucormycetes (formerly known as zygomycetes). The involved tissues turn red, violet and finally black due to tissue necrosis, forming black eschars, and so the disease has been given the name black fungus (kalo dhusi). Mucormycosis is a ubiquitous fungus present throughout the environment, especially in soil, animal dung, and decaying fruits and vegetables. The American Centre for Disease Control and Prevention says most people come in contact with microscopic fungal spores every day. People contract lungs or sinus forms of infection through inhalation of the fungal spores present in the environment, and skin infection through scrapes, burns or other types of skin injury. The infection is a life-threatening disease; with recent Indian experiences putting the fatality rate at 45.7 percent.

An opportunistic infection mainly affecting immunocompromised people, mucormycosis is of four types. The rhinocerebral type, most commonly seen in patients with uncontrolled diabetes or kidney transplants, is the infection of the sinuses which may spread to and damage the eyes, upper jaw and the brain. Pulmonary infection is common in people with cancer and in people who have had an organ transplant or a stem cell transplant. Gastrointestinal infections are seen mainly in infants who have had antibiotics, surgery or immune-suppressing medications. Those whose immune system is not compromised may show cutaneous infections if the fungus enters through a break in the skin.

In India and the United States

Epidemiologists are trying to explain the reasons behind the surge of mucormycosis in India and not in Europe or the United States. Both India and the US have a high number of diabetics (77 million and 34 million respectively), but the prevalence of undiagnosed and uncontrolled diabetes is higher in India (42 and 77 percent respectively) compared to that in the US (21 and 18 percent respectively). In terms of health complications and opportunistic infections, it is the number of undiagnosed and uncontrolled diabetics that matters, and this is where India and the US are different. In terms of immune status, 3.6 percent of the US population is immunocompromised, while the figure is 20.8 percent for Indians. This means, compared to Americans, Indians have a six-fold greater chance of contracting mucormycosis. Obviously, this is the major reason for the surge of mucormycosis in India and not in America.

Now, come to the socio-economic status. The low economic status of the average Indian results in less prompt healthcare, consumption of fruits that are almost over-ripened or rotting, increased exposure to soils, organic dirt and manure, and congested and sometimes mould-growing damp housing. All these contribute to fungal infections. Writing in Czecho-Slovak Pathology (2020), Dr Aparna K Sanath and co-authors at Teerthanker Mahaveer University, Moradabad, Uttar Pradesh reported a case of mucormycosis occurring in a 42-year-old immunocompetent male patient. They attributed the infection to poor socio-economic status and local trauma caused by an unhygienic setup or poor health care.

Dr Jenna Blah Bhattacharya and colleagues, while reporting a case involving an 11-month-old male infant with oesophageal mucormycosis in New Delhi in 2015, mentioned in the Biomedical Journal (2016) that proper weaning practices had not been performed due to poor socio-economic status. Writing in the Indian Journal of Ophthalmology (2003), Nithyanandam and co-authors stated that an unusually high incidence of rhino-orbito-cerebral mucormycosis at St John’s Medical College Hospital, Bangalore could be a reflection of poor diabetic control, poor socio-economic factors and low level of patient education and awareness. Dr Monasar S Al-Muflahi of the Medical College of Hadramout University, Yemen has written in the Suez Canal University Medical Journal (2014) that there is a positive correlation between fungal infection and low socio-economic status which accounts for 56.25 percent of fungal sinusitis.

We will not discuss the association of immunosuppressants in subsequent fungal infections, as it has been already recognised in medical science and is widely accepted. Let us look at the use of immunosuppressing medicines in the management of Covid-19. Many medicines with immunosuppressive activity have been used in the management of Covid-19, including some as a continuing therapy against pre-existing health problems such as lupus, rheumatoid arthritis and multiple sclerosis. They consist of conventional DMARDs (disease-modifying anti-rheumatic drugs), and in case these are ineffective, biologic DMARDs. These and many other reports point to the occurrence of mucormycosis in the past, independent of the present coronavirus pandemic. Covid-19 may have exacerbated the existing socio-economic hardships, provided an opportunity to the fungus, both through lockdowns and the use of steroids and other immunosuppressants.

Industrial oxygen and masks

There has been widespread speculation that the administration of industrial oxygen is responsible for the mucormycosis in patients following Covid-19 therapy through the passage of dirty water and soil. Hygiene is certainly an issue. Unhygienic practices can do harm to the patients in many ways. However, there is no evidence of the fungus growing in water in the first place. Secondly, the fungus is unlikely to grow in hyperbaric oxygen. Studies, including one started by the Karnataka state government, are underway to see the link. So we should wait until the evidence is produced.

Obviously, dirty masks can be a factor. Writing in The Pediatric Infectious Disease Journal (2014), Dr Jonathan Duffy and co-authors showed that mucormycosis outbreak was associated with hospital linens, and recommended that these should be laundered, packaged, shipped and stored in a manner that minimises exposure to environmental contaminants. For the time being, adhering to established health and hygiene practices, including using masks at dusty construction sites, wearing full body-covering dresses, avoiding direct contact with dirt and manures while at work, and avoiding rampant self-intakes of iron and zinc supplements, can help.

21.12°C Kathmandu

21.12°C Kathmandu