Columns

A Buddhist nun in the 1950 revolution

Dharmashila Anagarika’s story is one of courage and nous, especially at a time when few Nepali women could participate in the public sphere.

Amish Raj Mulmi

A city, in many ways, resembles a living being. It grows organically as more and more people come to live in it. Like all living beings, it responds to those who settle within its environs, and when it falls off the map and people begin to migrate from it, it dies a slow death. But once a city reaches critical mass, it becomes an unstoppable object, subsuming everything and everyone within its limits, and sometimes even its stories. Its many histories begin to coalesce into a larger mythos, and even those who grew up in it have to dig out some of these stories.

While growing up in Pokhara in the 1980s and 90s, these thoughts, however, were relegated to the future. At that time, Pokhara was a town; about 80,000 people lived there in 1989. Although the old town areas down south from Bindhyabasini temple remained the locus, trade and commerce had begun shifting to the Mahendra Pul and Chipledhunga markets. But when you think about the fact that in 1952-54, Pokhara had a population of just 3,755, one is simply astounded by its pace of growth. By 2013, Pokhara had grown nearly a hundred times, and the population had reached 272,830, a number that would surely be higher today.

Despite the population growth and Pokhara’s commercial and economic importance in Nepal, much of its history has fallen under the shadow of Kathmandu. One of these tales is about the 1950 revolution, whose popular narrative usually excludes the revolts that had erupted all across Nepal’s towns. While Lokranjan Parajuli has done a detailed study of the formative period of the 1950 revolution in Pokhara, my own interest comes from the fact that my grandfather, Prem Raj Mulmi, played an active part in fomenting and nurturing anti-Rana opposition in Pokhara. Then there’s the story of Dharmashila (also titled as Dharmamitra by Ernestine McHugh in her 2001 ethnography) Anagarika, one of the most fascinating characters in Pokhara’s history, and certainly one of the bravest.

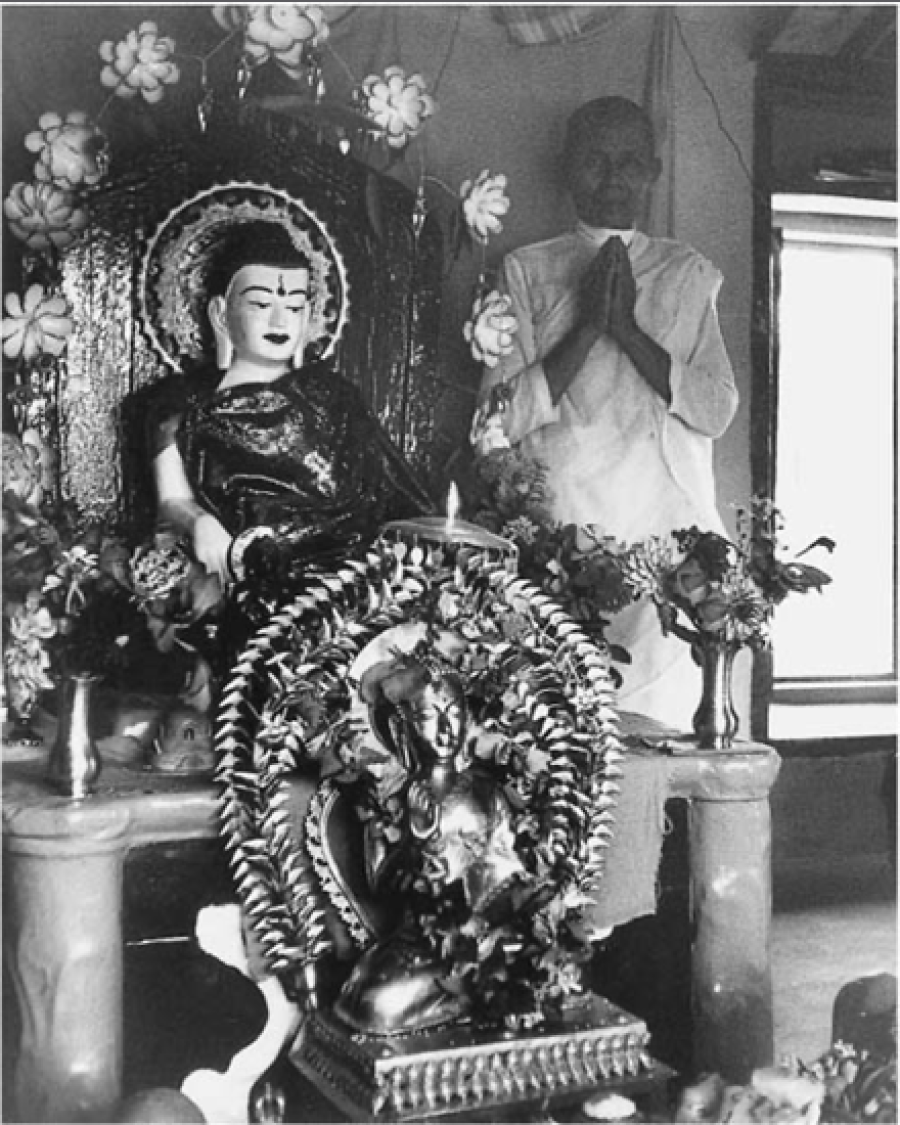

I first came across Dharmashila’s tale in Jagannath Adhikari and David Seddon’s Pokhara: Biography of a Town (her title is spelt as Anarika in the text). Her monastery in Nadipur was a hub for political activity where nascent revolutionaries would gather, hidden away from the gaze of Rana governor Dhan Shamsher. Theravada Buddhism had been targeted by the Ranas, who forbade its practice and dissemination, and several monks had been exiled, too. But Dharmashila, who was born as Setimaya Tamrakar, ‘helped to organise the underground meeting of the prominent freedom fighters of Pokhara region’.

The 1950 revolt in Pokhara was spearheaded by several young men, and Nepali Congress activist Hari Prasad Sharma played a vital role in bringing them together. Sharma had disguised himself as a holy man (and came to be known as kana baba) in an effort to recruit individuals for the anti-Rana struggle. But as the number of dissenters grew, Sharma was arrested. A notebook was found upon him, and based on the information within, several individuals were arrested, including Dharmashila. She became the first woman political prisoner in Pokhara after being imprisoned for nine days.

My father tells me she regularly visited our house in Pokhara until her death in 1987; she and my grandmother were friends, perhaps through my grandfather’s political antecedents. The ethnographer McHugh draws a tender portrait of her: ‘In Pokhara, Dharmamitra was alone. Nuns from Kathmandu visited on occasion, but she was a one-woman organisation, defining her role in her own terms…she was also the most senior nun in Nepal, first among all the living women of the Theravada tradition there. In the Buddhist orders, all monks are considered senior to nuns, but in Pokhara there were no monks. Just Dharmamitra’.

McHugh writes of how Dharmashila decided to become a nun after being influenced by travelling monks, but her upper-caste Newar family was horrified. ‘They were a wealthy Hindu family, important in the town. To hear the teachings of holy men was good. To send your daughter to be a nun in a foreign religion was bizarre’. But Dharmashila was undeterred. She went away with the Buddhist teachers to Kushinagar in India, where she was ordained. When she returned, she practised and spread the religion without a monastery until 1941, when one of her followers gifted her the land in Nadipur, where she set up the Dharmashila Buddha Vihar.

Anagarika was known as ‘Guruma’ in town. McHugh writes, ‘Dharmamitra had power. It grew out of chance, daring, and her imagination… She had a following but she dealt with them with a light touch. She was welcoming, not pretentious. She had a ready laugh. Her robes were different in that they slightly resembled a sari in the way they were wrapped: distinctive, but close to normal women’s dress’. Then in 1987, when McHugh returned to Pokhara after five years, she learnt Anagarika had passed away of cancer a few months previously. ‘I felt fatigue and a sense of vertigo, waves of grief and nausea’.

Discovering Anagarika’s story, in many ways, was a recollection of my own formative years in Pokhara. I was fascinated by her nous and courage. And it was a reminder of the many stories that shaped this city I had grown up in. For many years I travelled back home only during vacations; as Pokhara grew around me, I barely noticed it. But now, when I return home, the city becomes something else, a living being that has undergone a wave of development. I see new homes and new localities—places I had barely registered as being within the town’s limits. As histories of the personal and the impersonal come together, I suppose this is the sort of nostalgia that leads one down memories, when the past becomes not just ink on paper but also a souvenir to hold on to.

16.12°C Kathmandu

16.12°C Kathmandu