Columns

What does China want from Nepal?

China’s interests in Nepal have evolved over the years. It has never been as politically invested as it currently is.

Amish Raj Mulmi

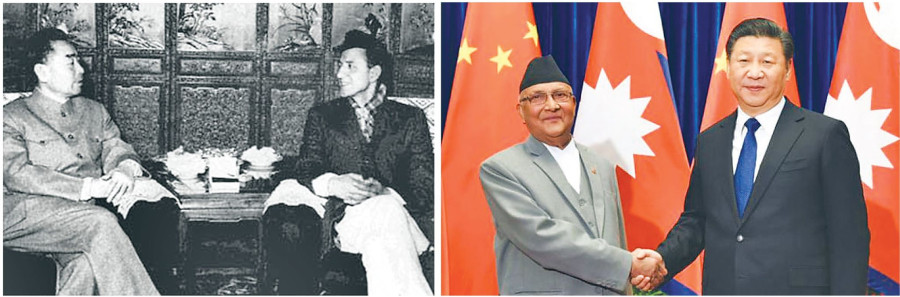

Sixty-five years to the day that Sardar Gunja Man Singh and Ambassador Yuan Zhongxian signed the agreement and established diplomatic relations between Nepal and the People’s Republic of China, Kathmandu’s turn to the north is more of a reality now than ever.

Nepal has viewed China from two primary lenses: one, that China provides political and international backing against a hegemonic India; two, that Nepal can profit from China’s economic progress, through aid and investment, and thus can become an alternative to Nepal’s landlockedness vis-a-vis India. Both views are rooted in the ‘China card’—a predisposition to look towards Beijing only when relations with Delhi are at a low, as currently—which Beijing analysts have long decried.

While reams have been written by Nepali scholars analysing what China can do for Nepal, rarely has the discourse shifted towards what Beijing wants from Kathmandu. For, unlike Nepal’s unchanging discourse vis-a-vis China, Beijing’s approach has constantly evolved over time as its own ambitions have grown. Beijing’s view of Kathmandu also parallels its evolution as a world power; there is a noticeable shift only when China’s own capacities to deal with infrastructural and other challenges have improved.

Evolution

In the beginning, Beijing’s primary concern was the 1856 treaty between Nepal and Tibet that dealt with the latter as an independent state. When the People’s Republic of China assumed control of Tibet in 1950, it needed to cancel all such past treaties that allowed Tibet a de-facto recognition of sovereignty. Thus, a Chinese Foreign Ministry document outlined the abrogation of the treaty as one of Beijing’s key issues with Nepal just before the 1955 Asian-African Conference in Bandung, Indonesia.

The early Nepali democratic leaders were nervous about China’s moves in Tibet. BP Koirala told Jawaharlal Nehru he had ‘gifted Tibet to the Chinese on a silver platter’ after the 1950 agreement on Tibet was signed between India and China, and provided the template for Nepal’s own agreement with China on the matter in September 1956. Nonetheless, Nehru was being prescient when he told BP, ‘When all is said and done, [Nepal] will not be able to maintain [her traditional] rights in any case… Renouncing your rights, on the other hand, will send a positive message to the Chinese’.

Despite initial hesitations, Nepal and China initiated diplomatic contact in 1955 after a gap of more than four decades. Border negotiations with China were peaceful, except the Everest dispute and the Mustang incident. Soon, hostilities between India and China led to Nepal being sandwiched between the two powers. The era of competing for influence in Kathmandu had begun. China’s offer of a trans-Himalayan highway till Kathmandu was both in alignment with Mahendra’s desire to pull away from Indian influence (and a message that Delhi could not continue to host Nepali Congress rebels on its soil), and with Beijing’s own need to find alternative routes into Tibet.

With the Cultural Revolution, relations went into a deep freeze, as Nepal fought back against Red Guard propaganda. After the Sino-US rapprochement, Nepal cracked down on the Tibetan armed resistance, earning it brownie points from Beijing. But China also knew its own limitations south of the Himalayas. In 1975, Deng Xiaoping told the Americans that China’s role in Nepal was ‘limited’ at the time, but ‘perhaps things will get better when our railroad into Tibet is accomplished’. Deng’s 1978 Kathmandu visit was intended to send out a message to the world of a new China, even as Nepal’s own expectations from the visit could not be fully realised. ‘[T]he days when Nepal could ask China to compete with India in providing aid were over… The spirit of the Deng era was China first’.

The Tibet question

In the late 1980s, with the internationalisation of the Tibetan exile movement and the Tiananmen uprising, China faced tremendous international pressure from all sides. Its verbal support to Nepal during the 1989 Indian blockade came as a relief to Kathmandu, but implicit in the message was that China could only do so much for Nepal at the time. However, Beijing needed to quieten down Tibetan exiles, so when Nepal decided to stop issuing refugee certificates to Tibetans in the mid-1990s, China was relieved. Under the presidencies of Jiang Zemin and Hu Jintao, securing the Tibetan frontier—as China shifted its lens westwards under the ‘Open up the West campaign’—became a key issue of national security. Nepal, in turn, because of its large number of Tibetan exiles and porous borders, became important in such calculations.

As such, even as China decried the Maoist rebels as bandits ruining the name of their great leader, Beijing began to engage the monarchy and security agencies more and more. In 2002, Nepal cancelled three different events in Kathmandu marking the Dalai Lama’s birth celebrations, the first such reported instance. When the US and India refused to supply King Gyanendra’s autocratic regime with military aid, China stepped in. But as the royal regime began to be hemmed in from all sides, Beijing began to engage with all political actors, including the Maoists. Then, in the run-up to the 2008 Olympics, as Tibetan protests became a daily occurrence in Kathmandu, Beijing invested heavily in engaging Nepali security forces. A slew of aid and agreements followed; by the time Xi Jinping ushered in a more expansive neighbourhood policy in 2013, China was more assured and confident about controlling Tibetan activities in Nepal.

The future

Now, as the US-China contest sharpens, Beijing’s expectations from Nepal can be best read in Xi’s op-ed, published before his visit, and the recent press release, post-Foreign Minister Wang Yi’s meeting with representatives from Nepal, Afghanistan and Pakistan. China would like to see limited Indian ambitions in the neighbourhood, and the 2015 Indian blockade was a most opportune moment it capitalised upon. Beijing has also never been as politically invested in Nepal as in the present day. But despite these two issues, China is equally ambitious about reaching out to the massive Indian markets through Nepal; a recent op-ed by a former ambassador suggested the raison d'être for the train from Tibet would be such.

At the same time, China values Nepali support for Beijing’s position in international forums vis-a-vis the contest with US—hence the highlighting of Nepal’s support to the new Hong Kong laws; the emphasis on building solidarity against Covid-19 and not politicising the pandemic; and the continued push for BRI and other infrastructural pushes into the region. By doing so, China has positioned itself as a responsible world power that takes into account neighbours’ and allies’ interests—a moral high ground. It has also successfully couched its own interests within this discourse, as any world power will. But as China becomes more assertive politically and otherwise in Nepal, it will also be questioned as much, as we saw in the aftermath of the current ambassador’s meetings with Nepal Communist Party leaders.

The belief that China assists Nepal out of only neighbourly concern is naive at best. Its interests in the country have evolved over time, and so has its policy approach. Unfortunately, Nepal’s approach to the north has been motivated by the ‘China card’ approach. The question then is, can Nepal look beyond it?

11.12°C Kathmandu

11.12°C Kathmandu