Columns

Peace minus justice

The promises made under the Comprehensive Peace Accord have been thrown to the winds..jpg&w=900&height=601)

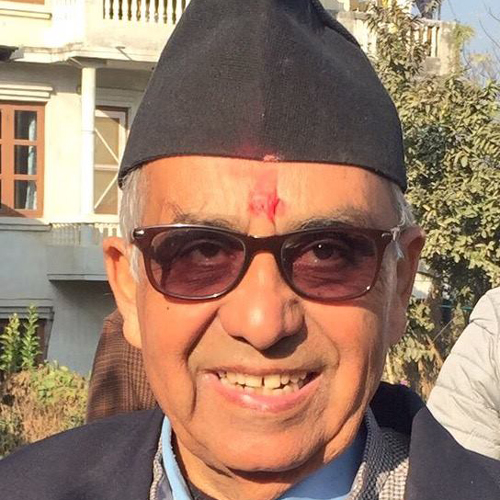

Daman Nath Dhungana

Some issues concerning Nepal’s peace process have drawn serious public attention. Prominent among them are tendencies such as going back on the promises made under the Comprehensive Peace Accord and evading immediate obligations, particularly concerning different aspects of transitional justice. The then prime minister the late Girija Prasad Koirala and Maoist leader Prachanda signed the pact in November 2006 with the sole objective of bringing a decade-long war (1996-2006) to an end and fostering a conducive environment for national reconciliation.

The accord encompasses a very wide area of national reconstruction and humanitarian services. It covers vast areas of activity beginning from relief, repatriation and rehabilitation of victims to the composition of conflict managing tools, like commissions, to look into war-time human rights abuses. The pact also prescribes socio-economic transformation under state restructuring schemes including replacing feudal land ownership with a scientific land reform programme.

Rampant corruption

The accord, seriously taking note of the menace of rampant corruption in the country, calls the political parties to adopt a policy of severe punishment against those acquiring unjust wealth while holding government office. Above all, the accord directs the entire state machinery to refrain from encouraging impunity in all walks of life. It is an entirely different matter to what extent our political parties have enabled themselves to combat corruption and other social evils with missionary zeal.

Among the treaty provisions, disarming and demobbing the Maoist combatants was relatively best handled and finished, more and less, on time. More than 1,400 of the rebel fighters were ultimately integrated into the national army. This helped wind up the longstanding debate over whether the Maoist combatants should get a berth in the national army or not. It also raised questions like to what extent it was justified to let loose personnel skilled in the use of arms without a job guarantee. Besides the achievement in disarming and demobbing the rebels, sufficient power-sharing and active participation of the Maoists in the constitution-making process was well observed.

So it is a big surprise why transitional justice alone was left unattended, overlooked and even neglected, from the very beginning, by the negotiating parties. This has given adequate grounds to the human rights community to call this behaviour and inexcusable delay an act suggesting 'deliberate denial of the rights of war victims, encouragement to unaccountability and human rights violations'. While observing some key provisions and the extent of serious non-compliance with the promises, specifically with reference to Sections 5.2.3 and 5.2.5 of the Comprehensive Peace Accord, no sensible person would accept that kind of criticism as 'baseless and biased'.

It is so also because the pact directs the concerned parties in clear-cut words to immediately start conducting urgent tasks within a specified time: Make public the information about the real name, surname and address of the people who were disappeared by both sides and who were killed during the war and to inform also the family about it within 60 days from the date on which the accord has been signed; and investigate truth about those who have seriously violated human rights and those who were involved in crimes against humanity in course of the war and to create an environment for reconciliation in the society.

In light of the above directives, one can imagine the magnitude of the act of negligence that has been committed. Instead of the 60 days’ time given by the accord, the concerned parties have already and unjustifiably taken time, as long as 13 years, that is about 25 times more than the originally fixed time.

This stands as a perfect proof of the fact to what extent the parties in charge of the said responsibilities continue to be least interested and serious in or about the most urgent and topmost humanitarian task, such as transitional justice. It indicates, on the other hand, to what extent they are bent on keeping the task of constituting the commission hanging for an indefinite period of time in order to see evidences untraced and war victims fatigued.

Absence of fairness

Further, looking back, there is clearly no dearth of instances substantiating the absence of fairness, from the beginning, on the part of the parties responsible for appointing the commissions and disposing cases concerning different aspects of transitional justice within a reasonable time period. To begin with, the very draft of Reconciliation Bill was unreasonably delayed, it was not in tune with international standards even while it was passed by Parliament, the concerned commissions were constituted only after about seven years of the signing of the peace pact. Therein also the political parties were managing the results to appoint the members on the basis of loyalty to their party, thus obviously killing the very spirit of independence of the commissions from the outset.

Furthermore, the commission, even if constituted soon now, would not be able to expedite its work for the simple reason that successive governments have been turning a deaf ear to amending the concerned act despite the Supreme Court’s mandate to do so some seven years ago.

***

What do you think?

Dear reader, we’d like to hear from you. We regularly publish letters to the editor on contemporary issues or direct responses to something the Post has recently published. Please send your letters to [email protected] with "Letter to the Editor" in the subject line. Please include your name, location, and a contact address so one of our editors can reach out to you.

22.3°C Kathmandu

22.3°C Kathmandu