Columns

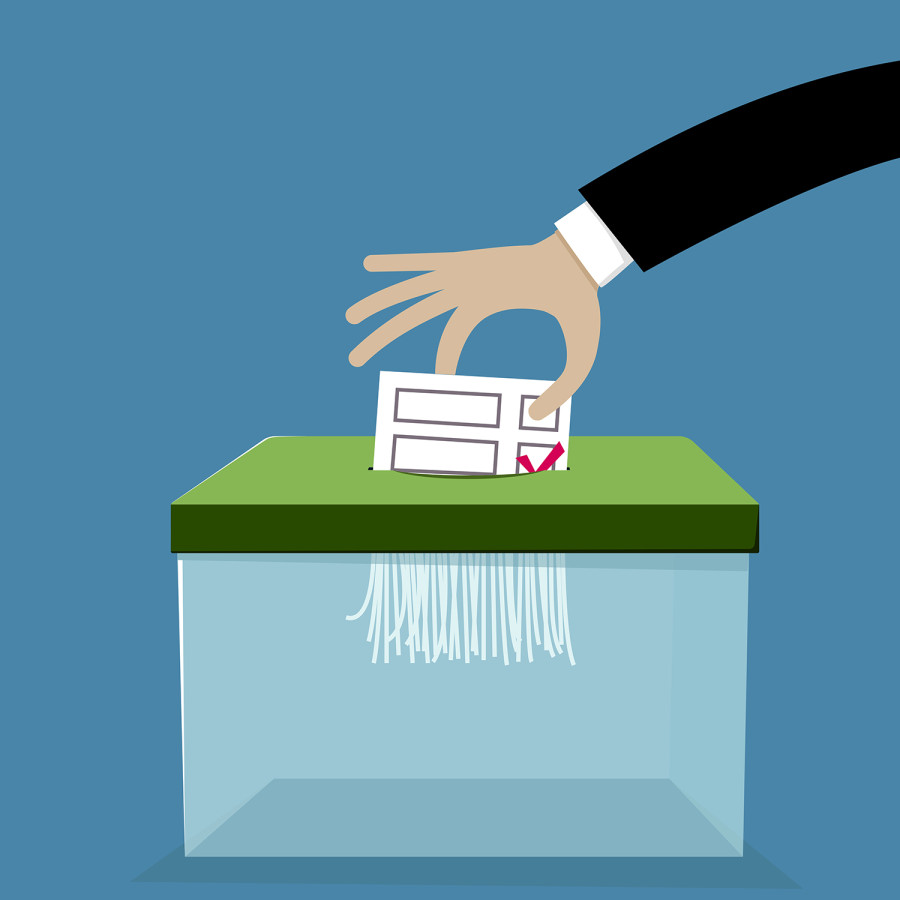

The elected undemocracy

Parliament has become a mere rubber stamp for all government bills that get sanctioned without any debate.

Achyut Wagle

The idea that Nepal is a federal democratic republic is rapidly disintegrating. The federal polity is effectively dysfunctional, and the concept of the separation of powers between the legislative, executive and judicial branches of the state has been trampled upon. Crucial political organisations—the pillars of any multi-party pluralistic democracy—are not being held accountable to democratic norms, values and practices, or to the constitution.

Orders from above

Last week, the standing committee of the ruling Nepal Communist Party decided to 'direct' the government and legislature of Province 3 to adopt Bagmati as the name of the province and fix the town of Hetauda as the provincial capital. This is a clear example how the very essence of federalism is being systematically truncated by the double-edged sword of the centre's inherent intent not to devolve power to the subnational levels coupled with the alleged inability of the provincial and local levels to exercise the power given to them by the federal constitution. This comes as the latest in a series of flagrant anti-federal tractions and jolts against the letter and spirit of the 2015 Constitution.

On the one hand, the federal government has been continuously expending its political capital to formulate laws that are clearly detrimental to the power-sharing arrangement under the federally restructured three tiers of government. Recent amendments to the forest and water resources legislation, and several other laws, clearly exhibit the deep-rooted intent to centralise power instead of releasing state authority to the lower levels. The federal government's unwillingness to fully functionalise the constitutional, legal and institutional arrangements made for a smooth and balanced operation of the federal system is extensively evident in multiple fields by now.

This, for example, includes the imperviousness of the federal government to complete even the appointments of professional members to constitutional commissions like the National Natural Resource and Fiscal Commission and to provide it true operational autonomy, and to carry out the provincial extension of the operation of the Public Service Commission, among several others. The government has been reluctant to formulate the required bylaws in public procurement, perks and remuneration of elected local executives, and the rule of procedure for them to avoid conflict of interest in the public decision-making process.

On the other hand, both provincial and local governments are failing to assert their authority as enshrined in the constitution, and instead are succumbing to extra-constitutional infringement of the same by the central entities, both political and administrative. Even at the mid-point of their five-year tenure, four out of the seven provinces are yet to decide on their names and provincial capitals, which exclusively is the domain of the provincial assemblies. The ruling party standing committee, going far beyond its jurisdiction, is meddling in such constitutional matters and overriding the authority of the subnational units. This phenomenon known as 'tragic brilliance' in federalism literature will eventually lead to centralisation of almost the entire decision-making authority in the federal government, retaining only the 'skeleton' of a federal structure. Nepal now seems to be heading towards that end.

The parties are failing

Democracy is a rules-based interplay of a multitude of institutions and processes. Institutionalised internal democratic practices in the political parties is a sine qua non of democracy. But all major political parties of Nepal suffer from severe democratic deficit, factionalism, ideological dilemma, disgusting level of avarice, petty vested interests, and absolute lack of moral integrity in the top leadership.

The ruling Nepal Communist Party has been a hostage to its own indecision over picking a candidate for speaker of the House of Representatives, which has impacted regular House business. In the absence of a binding and practically relevant ideology, the power struggle in the party is centred on 'distribution of lucrative opportunities' to influential leaders. Leaders defeated in the first-past-the-post elections have again been fielded as candidates for the Upper House election. The federal parliament has become a mere rubber stamp; all government bills get sanctioned without any debate.

Nepali Congress, the main opposition party, is in no way different. Its role as an effective opposition has been nondescript, mainly due to its small number of parliamentarians coupled with lack of a political strategy to censure the government’s excesses. Infighting between the establishment and anti-establishment factions in the party is at its height. Small and regional parties have also failed to register their presence with a creative political agenda for the future.

There are a few common tendencies in all the parties that have made them essentially undemocratic, both in form and function. The leadership, mainly in the ruling and main opposition parties, is still in the grip of the same people who led the popular pro-democracy movement in 1990. The pervasive gerontocracy in the entire political spectrum has been the source of an effective dictatorship within and without the parties. Despite rampant public apathy, the old hawks are not prepared to give way to fresh faces to assume responsibility in the party or government. In fact, these parties have failed to groom the younger generation of leaders that are better versed in contemporary political priorities and globally-accepted practices. This has resulted in utter disinterest in politics among the younger and educated segment of the population. Due to this indifference, the government is not worried about potential retribution even if it curtails democratic freedoms like the ones now being introduced through an amendment to the legislation pertaining to Information Technology.

Like an empress

The republic, in essence, is more 'rule by the citizens or public' than the form represented by an elected president as head of state. These days, more often than not, the demeanour of President Bidya Devi Bhandari is being seen as pompous, like that of an empress. Her quest for luxury, as shown by the expansion of the presidential palace by ejecting the adjoining National Police Training Academy, and her love for elaborate motorcades during her outings, is antithetic to the official national goal identified by the constitution as orienting Nepal towards socialism.

In a nutshell, before bringing the three political fundamentals—federalism, democracy and republicanism—back on track, Nepal's desire for durable peace, rapid progress and equitable prosperity cannot be realised. The course correction must start at the highest level of the political leadership of at least the ruling and main opposition parties of the country.

11.12°C Kathmandu

11.12°C Kathmandu