Columns

Ideology or evidence: What makes a policy?

Nepal’s case seems to be the antithesis of what economists would like to believe.

Mohd Ayub

Evidence-based policies have been the talk of the town in the last couple of months among economists and practitioners of global development after the 2019 Nobel Memorial Prize in Economic Sciences was awarded to three economists ‘for their experimental approach to alleviating global poverty’. These three economists are Esther Duflo, Michael Kremer, and Abhijit Banerjee who, by using a statistical tool called randomised control trials, generate evidences on how poverty-related policies can be drafted. Many economists and development practitioners, including Nobel laureates, have vehemently criticised the approach terming it to be misleading and short-sighted. The criticism leads to a compelling question: Do evidences really matter in formulating policies?

If historical evidences are anything to tell, it seems there couldn’t have been a more perfect time to award this particular contribution. The prize was awarded on December 10; on December 12 in the general election in the United Kingdom, the Labour Party seemingly went into an abyss. This needs some dots to be connected.

By 1997, the Labour Party had endured four consecutive defeats in the general elections and was out of power for a straight 18 years. This made them realise that their socialist inclined policies were getting in the way, so they transformed the party into New Labour that made very few promises, and rather were in line with the 'spirits' of the 'policies the conservative government had been pursuing'. When the party won a majority in 1997, it found itself facing adversities stemming from ideological leanings and a troubled economic legacy, especially for people in the lower economic strata, that were unleashed by Thatcher’s neoliberal economic policies. This made the Tony Blair-led Labour Party in 1997 to urge through a White Paper the policies to be made, backed by evidences and not by ideologies. Political commentators say that the Labour Party in 2019 didn’t learn from their past experiences as they promised too many things that made even some dedicated Labour voters to vote for the Tories out of fear that Corbyn ‘would bankrupt the country’. The Labour Party paid the price for ignoring the evidences they had.

It is said about ‘religious texts’ that ‘you can find anything you want in them—as long as you know what you’re looking for’. But shrewd observation suggests that ideologically driven issues are not immune from this irrationality and madness. In the early 1980s in the United States and the United Kingdom, a flatter tax rate—a tax rate more equally to be levied irrespective of the level of income—was implemented by president Ronald Reagan and prime minister Margaret Thatcher respectively.

The policy was passionately discussed by Arthur Laffer, and hence in public finance the model is called the Laffer Curve. Both Laffer and Reagan honestly maintained that the policy was not theirs; rather was borrowed from Ibne Khulladun, a 14th-century Muslim philosopher. Reagan even recurringly quoted Khalladun in his White House briefings 'at the beginning of a dynasty, taxation yields a large revenue from small assessments. At the end of the dynasty, taxation yields a small assessment from large revenues. This became the basis of flatter taxation in the US and the UK. But apparently, they both ignored the immediate next lines that read, 'The reason for this is that when the dynasty follows the ways of Islam...' which clearly means the policy prescription was meant for a different context—a context in which indulgence with usury is one of the most sinful acts, while the context (capitalism) where the policy was implemented revered indulgence with interest.

One of the key criticisms of the approach has been that the evidences do not matter much, rather other factors do. Back in the 1960s and the 1970s, in six US states and Canada, one of the biggest human experiments was conducted to assess the effectiveness of Negative Income Tax. Negative Income Tax intended to supplement the income of people earning less than a stipulated income through unconditional cash transfers. The experiment aimed to understand the extent to which people would stop working once they start receiving free money. The findings suggested that the drop in work was very small, and that the pilot could be extended nationwide. However, an unexpected result was found: Women who were enduring abusive marriages started coming out as they had become economically independent. Due to this, the proposed policy was termed as 'toxic to the American family' and eventually the whole scheme was 'nixed'.

This echoes with what happened very recently in India: The evidences collected by Banerjee and Duflo suggested there was a need to include eggs in the government’s midday meal programme. But for ideological reasons, it could not be translated into policy.

If the very aim of understanding what causes poverty and how it can be addressed is the underlying reason for having such an experimental approach, there seems to be another set of evidences that suggests we may not need it. Let’s take the case of Nepal with its spectacular achievement in poverty reduction from ‘everyone in Nepal is poor except for a few professionals and businessmen and perhaps some large farmers’ in 1979, as quoted in Devendra Raj Pandey, to only 21 percent poor in 2015. Nepal not only has demonstrated remarkable achievement on income poverty; it has also performed remarkably on the Millennium Development Goals.

Nepal’s case seems to be the antithesis of what economists would like to believe: Growth is key to poverty reduction. Nepal never got to enjoy stunning growth in the last three decades when this accomplishment was made. On top of that, for the same period, it endured a civil war and political instability. Of course, the major credit for this achievement is attributed to the personal remittances sent back from the countries where Nepal’s youth go in search of work.

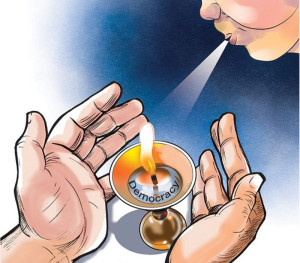

The pursuit of evidence-based policy is nothing but an ideological approach finding its roots in neoclassical economics-driven experiments that reemphasises market supremacy. This reasserts that poverty traps emerge due to the failure to make the right choices and eventually blames the poor while it ‘tends to ignore the broader macroeconomic, political and institutional drivers of impoverishment and underdevelopment’. However, both Nepal’s experience and Negative Income Tax’s findings suggest that people make decisions that collectively help them to flourish. Narrowing down the sources of evidences to some randomised trials with a presumption that the poor are the people who lack the ingenuity to make fitting decisions to come out of poverty is not only misleading, it is rather dehumanising. When people have money, they demonstrate a higher intelligent quotient than when they were out of cash. Policies stemmed from such short-sighted trials may only provide short-run remedies.

***

What do you think?

Dear reader, we’d like to hear from you. We regularly publish letters to the editor on contemporary issues or direct responses to something the Post has recently published. Please send your letters to [email protected] with "Letter to the Editor" in the subject line. Please include your name, location, and a contact address so one of our editors can reach out to you.

16.12°C Kathmandu

16.12°C Kathmandu