Culture & Lifestyle

On reading Durga Lal Shrestha as a family by candlelight

In an admittedly unpractical way, I sometimes wish for the absolute darkness imposed by routine power cuts. There is something fascinating about entire communities being plunged into the slow, deliberate rhythm of a dimly-lit world.

Sanjit Bhakta Pradhananga

Our homes don’t have khyaas anymore.

I came to this obvious conclusion the other day as I tried, unsuccessfully, to relay the terror of a Dhaplan Khyaa to my three-year-old nephew on what had seemed the perfect evening for such an initiation.

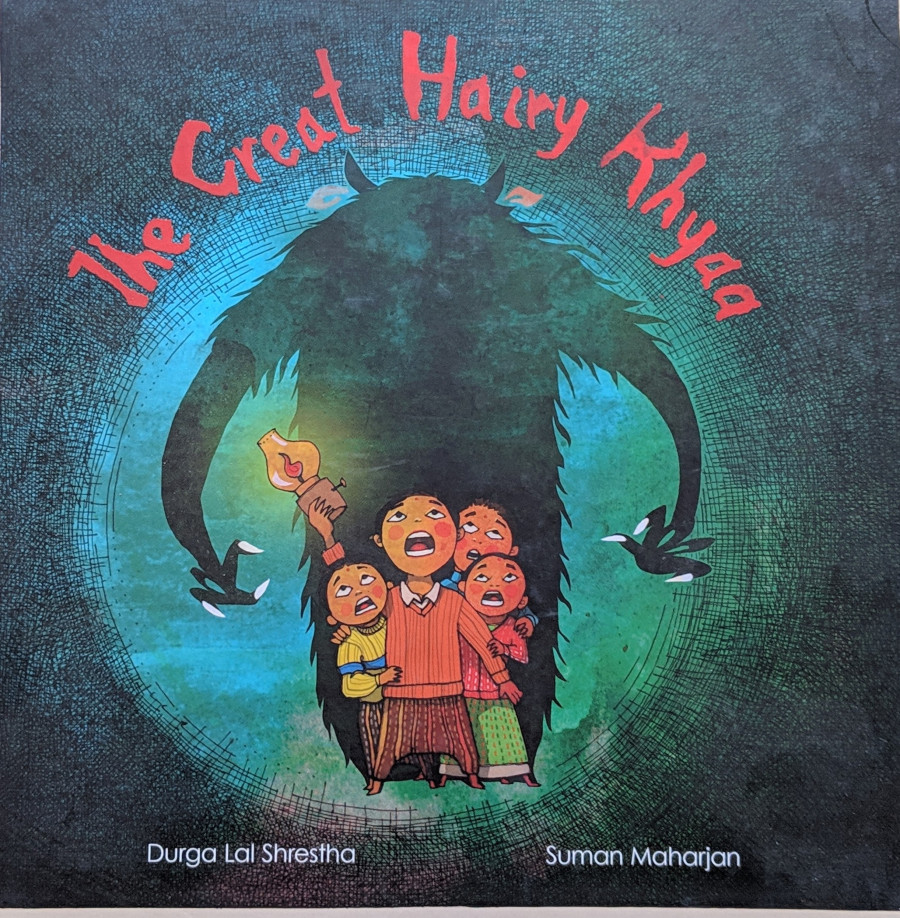

Huddled around a candle on a now-rare loadshedding evening, I was reading to him about the hairy, ape-like, sweet-toothed khyaa from a new collection of children’s books by Durga Lal Shrestha. The book, accompanied by some great illustrations by Suman Maharjan, had seemed like a perfect segue to introducing a myth so central to our imaginations as children. But as I struggled to read the Newar sing-along, it felt like it was more than just my poor grasp over Nepal Bhasa that was preventing me from scaring the kid as I had fully intended. My nephew—born and raised in a post-inverter era—just doesn’t have the same relationship with the dark that his mother and I did at his age. Quick with a smartphone or the light switch, darkness to him is never absolute, it is merely a momentary inconvenience. A suggestion you can dispel if you so desire.

I can remember a time when there still seemed to be more kerosene tukkichas at home than there were tungsten lights. Nights back then had a more infinite, abyss-like quality to them. This, of course, was greatly exaggerated by long and frequent power cuts in the city, but even without them, there remained spaces within the house that stayed completely dark from dusk through dawn—stuffy attics with cats whose yellow eyes scuttled among the shadows; damp chhyelins where khyaas lay in wait to trip you on your panicked hightail to the bathroom.

But our homes don’t have khyaas anymore. Author Jeanette Winterson goes as far as to propose that we don’t really even have nights anymore. In our fast-moving, fully lit world, she says, “Night still happens, but is optional to experience.” This is a world where electricity's triumph over the dark keeps us safer but also busier, where the 24/7 culture has slowly “phased out the night.”

In an admittedly unpractical way, I sometimes wish for the absolute darkness imposed by routine power cuts. There is something fascinating about entire communities being plunged into the slow, deliberate rhythm of a dimly-lit world. For fear of the dark might be something that cuts across time and cultures, but there isn’t much evidence to prove that nighttime is any more dangerous than the day (crimes are committed more often in broad daylight). If anything, darkness brings us closer. Around fires and candlelight, talking softly, between lingering pauses.

When I think about all the things that have changed in the glare of ubiquitous white lights, I can see why old nan’s tales like the Dhaplan Khyaa have slowly ebbed away from conversations. Private fears fuel communal myths and it is hard to spin a yarn about hairy humanoids in your basement when darkness conceals so little anymore. It is interesting that in Nepal Bhasa, the words khyuin (dark) and khyaa (and khwegu, to cry) play so closely off each other. So is it of any surprise that the slow erosion of the night has been a death knell for creatures that come to life with the failing light?

Which is why, I find Durga Lal Shrestha’s—that doyen of Nepal Bhasa literature—books come an ironic full circle in my candlelit room as I fumble through the words of a Newar sing-along intended for my three-year-old nephew. For decades, Shrestha has been at the vanguard of the struggle to give Nepal Bhasa a fighting chance in an increasingly homogenised world—his song Jhee Masini (We’re still alive) still serving as the de facto anthem for the Newa identity movement. But maybe it’s a little too facile to assume that languages die in the dungeons of a Kathmandu jail on charges of sedition for writing poetry, or at book burnings and the banning of indigenous newspapers. To think they are lost under the stranglehold of oppressive nationalism—eroding with time, through a process of persistent muffling and a gradual letting go.

Maybe deaths aren’t so spectacular after all. Maybe languages slip away a word at a time as you struggle to find words that don’t lend themselves to a changing world anymore. When they stop relating to our most primal fears, our most vulnerable selves. When they cease featuring in the stories we tell ourselves, and the ones we tell each other.

16.01°C Kathmandu

16.01°C Kathmandu

.jpg&w=200&height=120)