Can Nepal’s

viral

mayor run the

country?

Balendra Shah has proven he can win elections and capture imagination. His mayoral record suggests governing is harder.

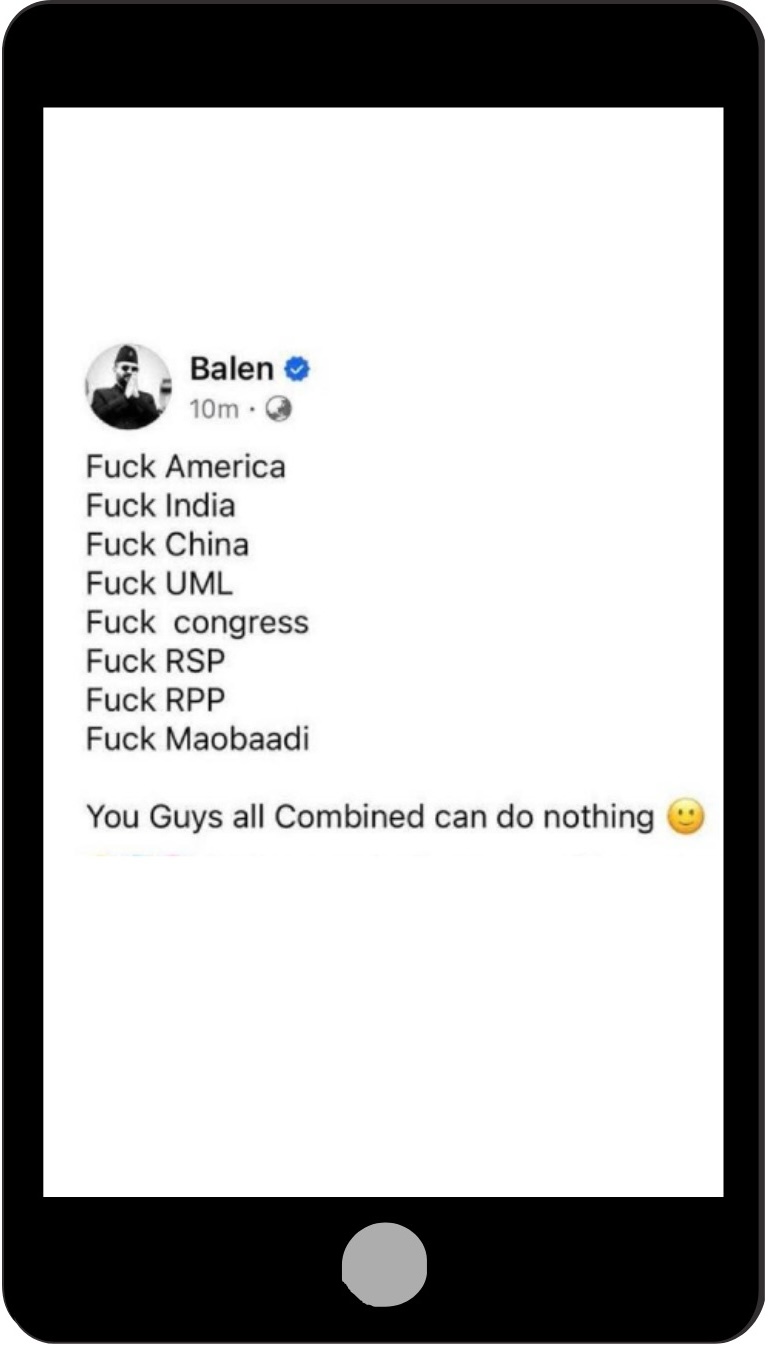

It was 11:56 pm on November 1, 2025, and Balendra Shah was sitting in a restaurant in Lalitpur, scrolling through his phone, when he decided to pick a fight with the world.

In a Facebook post that would be deleted within 30 minutes, Kathmandu’s mayor, popularly known as Balen, vented his fury not just at Nepal’s major political parties—including Rastriya Swatantra Party (RSP), which he would go on to join later—but at India, China, and the United States. “You guys all combined can do nothing,” he wrote.

Within 22 minutes, the post had drawn 34,000 reactions, 12,000 comments, and 1,700 shares. Most commenters criticised the language of the post studded with F-bombs. Friends called, urging him to delete it. He did, but not before thousands had taken screenshots.

The incident captures everything about Balendra Shah’s improbable rise: the outsider appeal that has made him one of Nepal’s most popular politicians, the combative instinct that won him the mayoral race in Kathmandu, and the impulsiveness that raises questions about whether he can actually govern beyond viral moments and bulldozers.

Now, Shah has been touted as the RSP’s prime ministerial candidate as he takes on former prime minister KP Sharma Oli at Jhapa-5—and that question has become urgent. Does this 35-year-old former rapper have what it takes to pull Nepal out of its political morass?

The answer, an examination of his three-year-long mayoral tenure suggests, is far from clear.

When Shah won the Kathmandu mayorship in May 2022 with 61,767 votes, defeating establishment candidates by thumping margins, he inherited a city choking on its own dysfunction. Illegal structures blocked ancient rivers. Commercial buildings flouted building codes with impunity. Pavements had been colonised by vendors and parked vehicles.

His response was swift and visible: deploying bulldozers.

In August 2022, he arrived at Alpha Beta Complex in Buddhanagar to enforce building codes, confronting property owners over unauthorised structures. His highest-profile campaign targeted underground parking spaces in commercial buildings that had been converted into shops and restaurants despite receiving tax incentives for parking. Municipal data showed at least 202 buildings in violation.

“There were gross violations all across the city—businesses being run in basement parking spaces and buildings being built without any design approvals,” said Nabin Manandhar, the spokesperson for the Kathmandu Metropolitan Office.

According to Manandhar, the majority of such buildings have been removed (he wasn’t able to share a specific number) and those that refuse to comply are under monitoring by the city office.

After a 35-day deadline, Shah authorised demolitions, reportedly targeting even a structure owned by one of his friends, a move that earned him praise for consistency and criticism for inflexibility in equal measure.

Shah then launched efforts to uncover the long-buried Tukucha river, demolishing structures to reveal its flow. He led drives to clear pavements in Basantapur, Thapathali, Baneshwar, and Koteshwar. Municipal officials credit his administration with removing illegal hoardings, expanding ambulance services, and introducing reforms in public schools.

Historically, Kathmandu’s private schools had been accused of distributing scholarships based on nepotism and favoritism. After taking office, he initiated an online application system where any student can apply. The city office now vets those applications and scholarships based on merit, talent, social disadvantage, and prior attendance at government schools.

“The transparency adopted in scholarship schemes in Kathmandu Metropolitan City’s schools is among the local unit’s important initiatives,” said Surendra Bajgain, who oversaw education, health, social affairs, environment, and disaster management during Shah’s tenure as mayor. Bajgain is currently campaigning for Shah.

But demolition is easier than construction. And this is where Shah’s record gets murkier.

Kathmandu’s budget absorption rates—the percentage of allocated funds actually spent on projects—remain among the lowest of Nepal’s major cities. The metropolitan city had allocated Rs25.76 billion for the current fiscal year. According to the city’s statistics, only about Rs4.64 billion of the allocated budget has been spent. The recurrent expenditure stands at 28.44 percent, while capital expenditure is at 12.39 percent. Even in previous fiscal years, Kathmandu has ranked lower than other metropolitan cities in terms of budget utilisation.

Critics cite this as evidence of mismanagement. “The low spending of the city is the result of insufficient preparation and improper project selection,” said Dilliraj Khanal, coordinator of the Public Expenditure Review Commission. “Even after the projects began, procurement and project development was not handled efficiently.”

As those critical preparations and planning didn’t happen, according to Khanal, there was an increase in cost, work was incomplete, and funds accumulated over time. “This is the result of people’s representatives not working in a responsible manner,” he said.

Shah’s defenders attribute it to bureaucratic obstruction and procedural complexities he inherited. The truth likely lies somewhere in between. But the gap between symbolic action and institutional delivery is real.

Perhaps most tellingly, Shah’s administration left its own employees unpaid for months during a prolonged dispute with chief administrative officer Saroj Guragain.

On December 21, 2024, the Metropolitan City held a press conference accusing Guragain of approving the blueprints for the Kathmandu Tower at the old bus park without following due process. The city even wrote to the Commission for the Investigation of Abuse of Authority to initiate an investigation against him.

After being asked to resign, Guragain stopped attending the office and another official was given the role of acting chief based on seniority. Paudel, who was nearing retirement, resigned shortly after, leaving the city without administrative leadership.

Following this, the Kathmandu Metropolitan City requested the federal government to send a new administrative officer. However, the government led by Oli did not send a replacement; instead, they decided to retain Guragain.

This decision escalated tensions—locally and at a national level. When Guragain tried to report for duty again, he was blocked by the city police that reported to Shah. While the deputy mayor eventually de-escalated the situation, he was absent from the office that day. Weeks later, both Shah and Guragain would begin to reappear together in public gatherings.

Then there’s the street vendors.

Before his election, Shah campaigned with songs like “Garibako Chameli Boldine Kohi Chhaina” (No One Speaks for the Poor), positioning himself as a voice for the voiceless. As a teenager, he’d written a rap song about street children he saw on his way to school, moved by learning that many had never attended school and were living without family support.

As mayor, he launched campaigns focused on street children and child labour. According to municipal officials, Kathmandu Metropolitan City rescued 82 children from exploitative conditions and deployed 25 interns across 80 schools to study child labour patterns.

But vendors complain of confiscations and brutality by metropolitan police. One activist staged a 199-hour standing protest outside the metropolitan office. Agreements reached later remain partially implemented.

Arjun Bhattarai was one of those street vendors brutally beaten by the city police. In an interview with Kantipur, he said Shah turned a deaf ear to the pain of those who have no choice but to sell on the streets to make ends meet.

“Before the election, the mayor told us he would manage a place for us, but later, when we asked to be allowed to earn a living, I ended up with a broken head,” said Bhattarai. “Ultimately, it appears politicians like Shah don’t work for the common people once they win; they just forget their previous promises.”

Bhattarai, who hails from Mahottari, Shah’s ancestral district, said that following the city’s decision to clear the streets, many of his fellow vendors were displaced and some were forced to go abroad for work. “Now, they say we can operate after 7:30 pm,” he said. “Who is going to come shop at that hour in this cold?”

The contradiction was stark: the rapper who once championed the marginalised now wielded state power against them. Whether this represented pragmatic governance or betrayal of principles depends on whom you ask, and on whether the crackdowns actually solved underlying problems or simply relocated them.

“Someone who’s just arriving in Kathmandu might feel the city looks cleaner and more organised, but the real question is: who is this city for?” said Dr Pitambar Sharma, an urban planning expert and former vice chair of the National Planning Commission who holds a doctorate from Cornell University. “Is it only for the wealthy or also for the poor?”

Sharma pointed to examples of cities in the West, where there are designated times and areas for street vendors. “Kathmandu ended up with a mayor who doesn’t engage in dialogue with his citizens,” he said of Shah.

Others say that is just how Shah operates because he doesn’t relate to the style of the older generation of politicians.

“He never felt represented by the old political style,” said Milan Pandey, one of the co-founders of the Bibeksheel Party, which is seen as the incubator of alternative politics in Nepal, who met Shah three years ago and remains in touch with him. “He believed alternative forces could emerge if politics spoke the language of the people.”

But the question isn’t just about whether he will be different from KP Sharma Oli, Sher Bahadur Deuba, Pushpa Kamal Dahal—and many others who have taken turns to govern the country in the past. The question is whether Shah’s model—visible and dramatic enforcement campaigns, social media communication, personal brand over institutional coalition-building—can scale from municipal governance to running a country.

Balendra Shah’s political career did not begin in party offices or student unions. It began on the streets, and on the stage.

Long before he entered electoral politics, he was known among the younger generation as a rapper who used music to critique power and mobilise dissent. His 2013 song mocking police who launched a campaign against youths with long hairs accused authorities of harassing citizens instead of addressing real crime. When protesters were baton-charged in January 2015 during constitution-related demonstrations, he wrote “you can feel safe with terrorists but not with Nepal Police” on Facebook.

That same month Shah, then 24, released a new single ‘Ma Nepal Haseko Herna Chahanchu’ (I Want to See Nepal Smile). In an interview published in Nepal Saptahik at the time, he argued that music had historically accompanied political movements around the world, from Haiti to Gaza, and that rap could help connect Nepali youth to political change. He had been a constant presence at “We for the Constitution” protests in Kathmandu, often using rap as political expression.

“His songs were highly popular among young protesters,” remembers Narayan Kadariya, a campaigner who regularly invited Shah to programmes. “I personally invited him to join our programmes, and he never refused.”

The song only gained mass popularity after Shah’s mayoral victory, when its opening line began echoing across rallies and social media during the Gen Z movement last year.

That anti-establishment identity, forged through music, protest, and rejection of party politics, remains Shah’s greatest asset and his greatest liability.

When he finally entered the 2022 mayoral race as an independent, he did so with minimal resources but a tight-knit team. Figures with Bibeksheel backgrounds, including Bhupdev Shah, Saurabh Neupane, Sasmit Pokhrel, Shishir Banjara, joined the effort.

“In the early days, Balen would arrive on a scooter with his brother, carrying a microphone and pamphlets,” Banjara said. “Sometimes there were only five of us at a junction. As the mood changed, the crowds grew.”

According to Banjara, in the early days of that campaign three years ago, as he rode around on a scooter, they would introduce Shah as an engineer because many people couldn’t relate to a rapper.

Shah’s brother, Kaushal, remembers the crowd of followers during the mayoral race thin at the beginning. “This time around,” he said, signaling to his race in Jhapa-5, “his work as mayor in Kathmandu is already drawing thousands of people.”

His opponents have been consistently helping his rise, unintentionally. UML’s Keshav Sthapit, who had held two terms as Kathmandu’s mayor, made a series of controversial remarks during his mayoral run. At a discussion among mayoral candidates at National College in Dhumbarahi, a participant raised a question about allegations of sexual harassment leveled against Sthapit.

In response, Sthapit made an objectionable remark from the public forum: “You are a nice lady, but you speak a lot.” He also made inflammatory comments branding Shah a Madhesi. The Election Commission sought clarification from Sthapit about the election code of conduct. Neither the UML nor Sthapit responded.

Shah maintained a studious silence when all this was unfolding, allowing his opponents’ missteps to become their undoing.

But governing requires more than letting others self-destruct. It calls for diplomacy, negotiation, coalition-building, and navigating bureaucracy—skills that Shah has shown little interest in developing.

His communication strategy epitomises the problem. He rarely engages traditional media, preferring Facebook posts that sometimes spark controversy. Several of his statements are posted verbatim on social media pages like Routine of Nepal Banda (RONB), which help multiply his reach.

On occasion, posts about Shah on RONB were so consistent during his mayoral tenure that mainstream politicians accused of foul play. But RONB’s founder, Victor Paudel, isn’t shying away from the criticism. “We used to post about every candidate and political party, but those on Balen always got us the most user engagement,” he said.

While stories about Shah’s Facebook posts may have achieved record engagement, his late-night statements on geopolitics and governance have drawn criticism from analysts who warn of the responsibilities that accompany his popularity.

Shah has, at least until the time of publication, not made any appearance on national media since his mayoral victory to transparently present his governance or foreign policy strategies. Over the past several months, the Post has made multiple attempts to reach Shah for an interview, but we haven’t received a response.

Nabin Tiwari, a young political analyst, is more direct. “As the capital’s mayor and one of the country’s most-followed public figures, Balen should conduct himself responsibly on social media,” he said. “But at times, he makes posts on extremely sensitive issues, and you feel it would have been better had they not been written at all.”

The bureaucratic standoff with Guragain suggests similar patterns: an unwillingness to navigate institutional complexity, a preference for confrontation over compromise.

When the Gen Z movement briefly courted him as potential caretaker prime minister back in September, he declined, expressing reluctance to lead the country during the crisis. Yet he played a significant role in the formation of the citizens’ government that followed. Om Prakash Aryal, who had served as Shah’s legal adviser at the metropolitan office, became home minister. Army Chief Ashok Raj Sigdel was in regular contact with Shah, and his views were frequently sought during deliberations before Sushila Karki became prime minister.

However, after Karki assumed office as prime minister, Shah grew dissatisfied with both the government and the home minister. One of the points of contention is that Shah strongly believes the current government should hold former prime minister Oli accountable for the killing of protesters in September, a charge that is still under investigation by a high-level non-partisan commission.

The pattern is clear: Shah excels at mobilisation and disruption, and at influence without accountability. Whether he can build the coalitions and institutional relationships required for sustained governance remains to be seen.

Balendra Shah was born on April 27, 1990, in Naradevi, Kathmandu, in a household exposed to state institutions. His father Ram Narayan Shah, originally from Mahottari, was an Ayurvedic doctor who worked at Naradevi Ayurveda Hospital.

In a 2018 interview with Kantipur Television’s programme Call Kantipur, Shah admitted he’d been reluctant to attend school as a child. “I only began attending regularly after reaching Grade 3; even after that, I barely went,” he said in the interview. “By the time I sat the SLC examination, I still didn’t know how to write properly.”

His father often took him to meetings at ministries and government offices, where young Shah listened intently. Those experiences, his acquaintances say, sharpened his political awareness early.

He trained as a civil engineer, graduating from Himalayan White House International College in Kathmandu and completing a master’s in structural engineering from Visvesvaraya Technological University in India.

After the 2015 earthquake, he assessed damage to more than 2,000 houses across 14 districts and contributed to reconstruction projects in Kavre, Nepalgunj, and Gorkha. Shah has shared, at the time and over the past year, photographs on his social media account from those districts, but the exact nature of his work and how he contributed to reconstruction projects is not clear.

“At that time, I had the opportunity to study municipalities across the country—who is doing good work and why, and who is not,” he told Sanjay Silwal Gupta in a podcast interview in 2022. “Later, I also observed the work done by [current mayor] Chiribabu Maharjan in Lalitpur. He was in a minority in the municipal committee, yet there was cooperation when it came to doing good work.”

It was during reconstruction work that Shah began arguing publicly for technocratic governance—that doctors should lead the health ministry and engineers infrastructure portfolios. In the Kantipur Television interview, he suggested someone like him should be mayor.

When he ran in 2022, the scope was manageable: a little more than 300,000 registered voters in Kathmandu Metropolitan City. Municipal authority over building codes, pavements, local services. Opponents were familiar establishment figures running predictable campaigns.

Running Nepal, however, is a different proposition altogether.

The country operates under a federal structure with national, provincial, and local governments, a constitutional framework Shah has expressed ambivalence about. Though he has defended the current constitution as “the best available,” his past refusal to vote in provincial elections fuels debate about his commitment to federalism.

He did appear to make an about turn on his stance during a recent campaign rally in Janakpur, during which he hinted at empowering federal bodies. “You go to Kathmandu for pilgrimage, not to ask for your rights,” he said in Maithili, the dominant local language in the district. Whether this represents genuine evolution or campaign opportunism is impossible to say because Shah has declined requests for detailed interviews to clarify his position on a number of things.

National governance requires coalition management across parties, provinces, and institutional power centres. It requires navigating Nepal’s complex geopolitical position between India and China—the very countries Shah attacked in his late-night Facebook post.

Vijay Kant Karna, a former ambassador and a foreign affairs expert, highlights the sensitivity of Nepal’s geopolitical position. “Nepal’s geopolitics requires an understanding of the relationships we need to serve our national interests and priorities,” he said. “Balen cannot function in the role the way he did as a mayor of a city.”

Karna added that even before Shah’s nomination, RSP leaders have spoken about foreign policy matters with considerable restraint. Being the country’s top statesman, he said, isn’t just about striking a balance between two or three countries, it’s about driving engagement, bringing investments and building relationships and trust at political, bureaucratic, diplomatic, and even at a public level.

So far, Shah has given no indication he understands or is interested in this kind of complexity. His mayoral tenure suggests the opposite: a preference for unilateral action, personal brand over coalition-building, viral moments over sustained policy implementation.

Former government secretary Bhim Upadhyaya, who has a significant social media following, supported Shah during his mayoral campaign. “When everyone was yearning for change, I felt that a young person stepping forward deserved support,” Upadhyaya said. “He had come to meet me personally, and I found his agendas appealing.”

Upadhyaya says Shah is the only politician he’s ever openly supported. “Back then, Kathmandu was looking for young leadership,” he said. “Today, it is the country as a whole that is searching for a young leader.”

But youth is not the same as readiness. And the appetite for change that propelled Shah to power is not the same as the capacity to wield it wisely.

That gap is perhaps most starkly visible in Shah’s recent campaign. His tour through Janakpur, Jhapa, Ilam, and Taplejung drew eye-popping crowds. But the man who campaigned for Kathmandu’s city hall on a scooter three years ago was recently seen driving a black Land Rover Defender—the kind of luxury SUV that sells for upwards of Rs42 million (over USD 300,000) and turns heads even in Kathmandu’s ultra-wealthy circles. The vehicle immediately drew curiosity and criticism on social media: who owned it? How did he acquire it? A local noodle and spice tycoon told Kantipur he had offered the car to Shah for “some time,” but didn’t specify why or for how long. Shah’s secretariat released a statement saying the campaign had rented it. Days later, he abandoned the Land Rover.

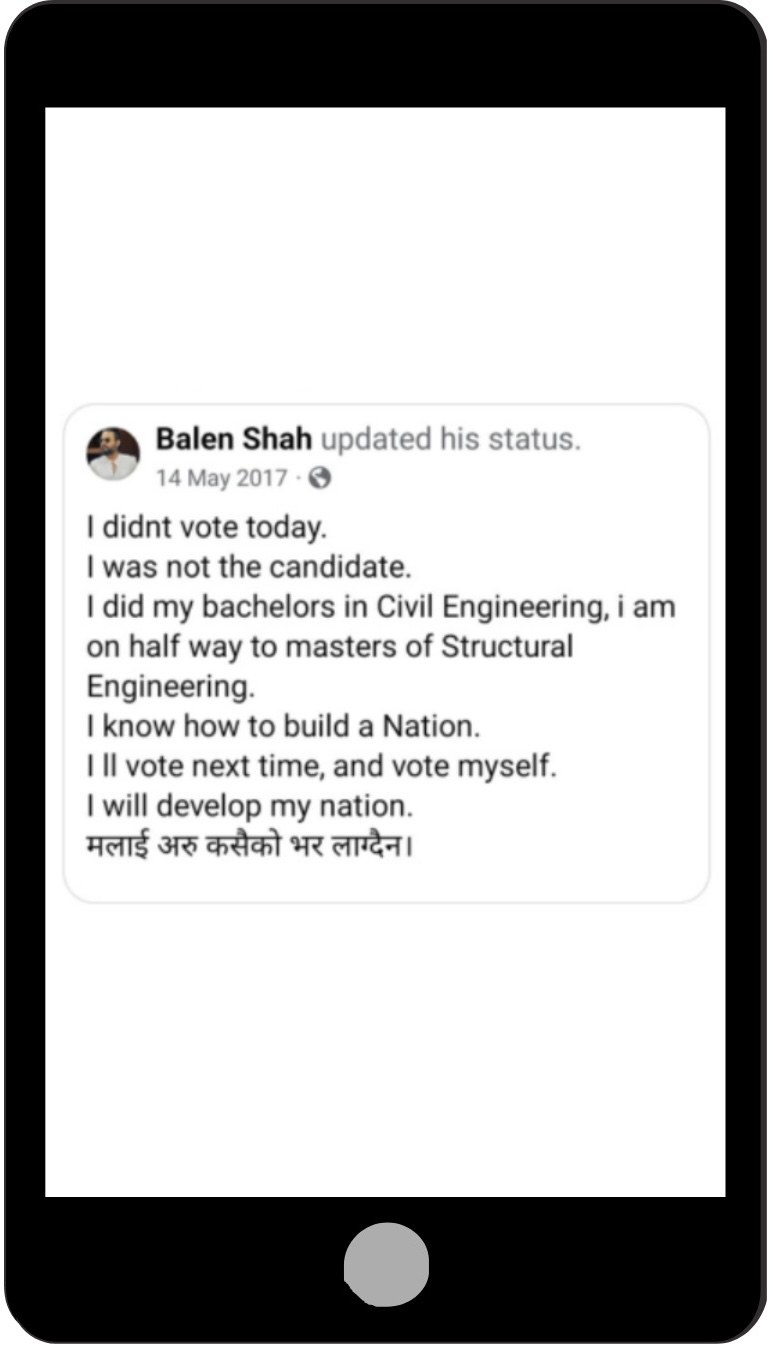

Seven years ago, when Nepal held its first local elections after promulgating a new constitution, Balendra Shah was a young voter from Gairigaun in Kathmandu who decided to abstain. He did not have confidence in the candidates.

”I will vote next time, and will vote for myself, because I know how to develop the country,” he wrote on his Facebook post on May 4, 2017.

Few took the post seriously at the time. CPN-UML’s Bidya Sundar Shakya won that election, with Nepali Congress finishing second.

Five years later, Shah made good on his promise—at the municipal level, at least. His victory symbolised a rejection of traditional politics, a hunger for alternatives, a belief that outsiders could govern differently.

Three years into his tenure as mayor, the results are mixed. He has delivered visibility, accountability in some areas, a sense that someone is finally willing to confront entrenched interests. The bulldozers are real. The scholarship transparency is real. The ambulance expansion is real.

But so are the unpaid employees (their salaries were held for 103 days). The abysmal budget absorption. The displaced vendors who have left the country in search of better lives. The bureaucratic standoffs. The impulsive social media posts. The preference for spectacle over institutional capacity-building.

Shah has proven he can win elections and capture imagination. He has not proven he can build institutions, manage coalitions, or navigate the kind of complexity that national governance demands.

Nepal’s political establishment has failed the country repeatedly. In just the past few years, Nepalis have witnessed major scandals—from the Bhutanese refugee scam to public land grabbing that implicated prominent political leaders. Large infrastructure projects built at the cost of billions of rupees from state coffers have had little utility. Public service delivery remains dismal. The hunger for alternatives is justified. But wanting something different and having a viable alternative are not the same thing.

Dr Sanduk Ruit, a veteran ophthalmologist and the Ramon Magsaysay Award laureate who has traveled across the country, sees Shah as a necessary corrective to Nepal’s entrenched dysfunction. “He has given hope to millions at home and abroad,” Ruit said. “But he cannot afford to repeat the mistakes of the old leadership.”

The question is whether Shah’s model—built on disruption, personal brand, and rejection of institutional politics—can evolve into something more than a compelling critique. Whether the rapper who wanted to see Nepal smile has the discipline, the patience, and the coalition-building skills to actually make it happen.

Based on his mayoral tenure, the jury is still out.