Miscellaneous

Significant rise in suicide after earthquake

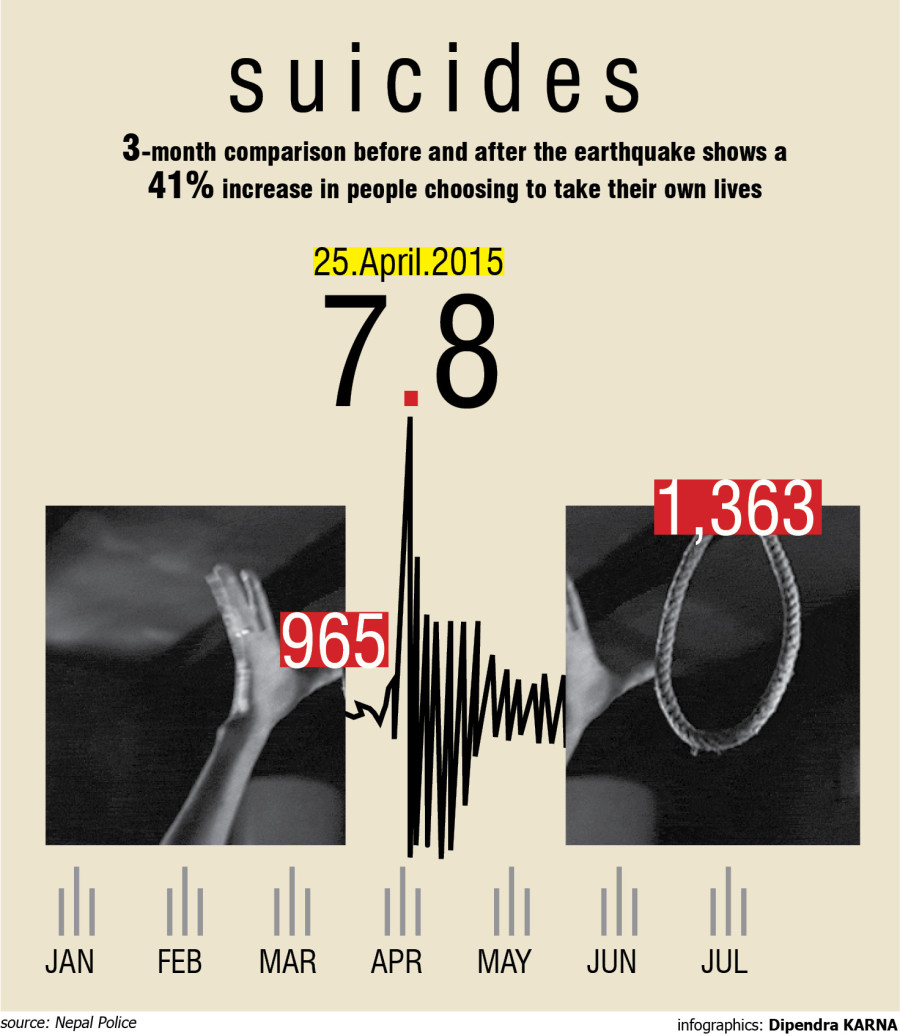

The data from January 15 to April 13 show that 965 had committed suicide, while the number rose to 1,363 in three months till July following the earthquake.

Manish Gautam

There is a significant rise in the number of people committing suicide, after the devastating earthquake of April 25 and subsequent strong aftershocks. A three months comparison before and after the earthquake shows that there is a 41 percent increase in people choosing to take their own lives, according to Nepal Police data.

The data from January 15 to April 13 show that 965 had committed suicide, while the number rose to 1,363 in three months till July following the earthquake.

"We observed that people were more insomniac, anxious and had chronic fear," said Dr Saroj Ojha, psychiatrist at the Tribhuvan University Teaching Hospital, who had visited Sindhupalchowk for counselling after the earthquake. "However, I should admit our system is yet to reach to as more people as we could. Had we reached these people, we could have saved their lives."

This appears to be a familiar pattern across the world: number of suicide cases spike after a disaster. Studies across the world show that there is increased suicide after floods, hurricanes or earthquakes. The papers basically state that people who have lost their loved ones and property are likely to remain mentally distraught that might proliferate into severe mental illness to a point where they choose to take their lives.

The World Health Organization estimates that 5 to 10 percent of people impacted by humanitarian emergencies will suffer from a mental health condition as a result.

Police data shows that over 4,000 commit suicide each year—which is four times more than people who die in road accidents. A total of 4,332 people committed suicide last year. Apparently more male resorted to suicide and with a majority of them choosing to hang themselves followed by the use of poison.

"The suicide rate is indeed alarming. Sadly, it has got far less attention and priority," said Deputy Inspector General of Police Mingmar Lama, chief of Women and Children Service Directorate at the Nepal Police Headquarters.

A report of World Health Organisation in 2014 stated that at least 15 people kill themselves every day in Nepal. The report titled 'Preventing Suicide: a Global Imperative’, showed that Nepal has the second highest per capita suicide (number of suicides in ratio to the total population) in South Asia after Sri Lanka. The WHO has outlined, among other factors, genetic and biological causes, disaster, war and conflict, stresses of acculturation and dislocation, discrimination and trauma or abuse to mental disorders, harmful use of alcohol, job or financial loss, hopelessness and family history of suicide.

While mental health has, in papers, got a little more attention than in the past, the government is yet to run intensive mental health programme. The programme that has been run so far remains scattered among various non-state organisations. The Ministry of Health and Population has only recently begun dealing in earnest with the issue of mental health including suicide in its National Health Sector Strategy, a five year government plan. This plan, which is not finalised, has included critical mental services in basic health package and gives priority to reducing suicides in par with reducing maternal and neonatal mortalities.

Jagannath Lamichhane, a mental health rights activist, considers the underlying socio-economic factors as the main reason for people to commit suicide. "The weak formal social safety net, underdevelopment and failure to provide adequate opportunity and access to basic services to people all contribute to the mental-health illness," said Lamichhane. "In earthquake, when they had no one to turn to, many people took suicide as an escape from witnessing devastation."

—

25.96°C Kathmandu

25.96°C Kathmandu