Culture & Lifestyle

Remembering the maestro Gopal Yonjan

Gopal was a trailblazer who shaped Nepali music—its present and future—disarming listeners, urging them to step into his realm of creations.

Anshrica Dewan

On a blazing hot Kathmandu day, Renchin Yonjan sits in her apartment surrounded by piles of labelled colour-coded folders. These folders contain newspaper clippings, interviews she conducted, and published work on her husband Gopal Yonjan. But more importantly, they carry proof of the amount of legwork she has done over the past 25 years to collect, catalogue and preserve her husband’s body of work.

Gopal Yonjan does not necessarily need an introduction but if he were to be introduced by his wife, Renchin, she would have the world know him as a poet, a man who could tame words into revealing their multi-layered meanings when teased.

“His early listeners appreciated and understood the songs he penned. They could hear the depth of the meaning they carried,” says Renchin. “Today’s audience is the kind that sees music rather than listens to it. Their entire attention is on the visuals. That’s why this generation and the future generation need access to his lyrics as they are.”

This is where her latest endeavour, a book titled ‘Gopalaya: Gopalka Geetharu’, comes in. To be released at an event, Gopalaya 22, in Kathmandu on Saturday, organised to commemorate Gopal’s 25th death anniversary, the book is a compilation of over 240 song lyrics written by Gopal between 1964 and 1997, including lyrics to Danfe Chari, a musical he wrote and composed in Darjeeling in the 1960s and recorded in Nepal in 1972.

“In this book, I have kept the lyrics clean. I haven’t mixed it with music. It would have been very easy to put notations next to the lyrics but I did not do that in the hopes that people who read this book really read, internalise and understand and get inspired by the words Gopal penned,” says Renchin.

A country without legacies to pass on to the future generation is a country on the verge of collapse; a society that does not have history preserved for posterity is a society deprived of a culturally literate future. Contextually, the book of lyrics is the first step towards correcting what Nepal has been lacking in documenting its cultural and literary heritage.

“If someone were to really study and research the lyrics, they will find a lot of layers to them. The historical, political and societal contexts are depicted through different songs like Bhani De Nepali Dai, Sab Jaga Jaga Bhanchhan, Birano Desh ko Mato Bhari, Laure and Andho, among others. Gopal’s songs are testimony to the rich and culturally diverse history of Nepal. If understood well, they can be a bridge between the past and the future for the current and next generations of Nepalis across the world,” says Renchin.

‘Gopalaya: Gopalka Geetharu’ couldn’t have come at a better time for Srijana Subba, a research scholar at the Department of Indian Languages, Banaras Hindu University, India. In 2019, when she was brainstorming research topics, her professor at the university, Diwakar Pradhan, suggested basing her research on Gopal Yonjan given the versatility in his work and his significant contribution to shaping Nepali literature across borders.

As a student of the Nepali language, Gopal’s song lyrics had a strong pull on her.

“But I didn’t know where to start because no documented materials were available about his contributions as a poet and lyricist. Most regard him as a composer, musician and even a singer but very few credit him as a songwriter, a poet,” says Subba. “I found a couple of his songs in cinema on YouTube so I would search and listen to a song and then try to separate his songs into music and lyrics. I was grasping at straws. But now that the book of lyrics is being released, I have a tangible source to continue my research.”

‘Gopalaya: Gopalka Geetharu’ has been divided into 11 segments—Philosophical, Patriotic, Spiritual, Ode to Women, Children, Cinema, Folk, Classical Dance Melodies, Thematic, Love & Romance, and Unrecorded.

This is a broad categorisation of Gopal’s songs, says Renchin, since the creator of the songs did not categorise his songs himself when he was alive.

“So the categorisation was done by me and my perception of what his songs mean,” she says. “Radio Nepal categorised the section carrying folk tunes into the folk genre but in actuality, these are not folk songs. They are based on folk music and folklore, but their composition has a distinct Nepali feel with different indigenous styles of music. For lack of a better word, I have categorised them into folk.”

Every single song penned by Gopal has multi-dimensional meanings but they carry a similar theme of self-reflection. “One of his songs, Mero Geet Mero Pratibimba Hoina, was written by Gopal when he was 19 or 20 years old, hinting at the spiritual awakening he was experiencing at that moment,” says Renchin. “In the Spiritual segment, you’ll read the lyrics of Har Naad which is more of a conversation between him and the higher power. In the song, he acknowledges Saraswati and credits her for whatever he is. But he does not ask anything in return for his prayers to her. His songs are deeper than what could be perceived on the surface.”

Kathryn March, Professor Emerita of Anthropology, Feminist/Gender/Sexuality Studies, and Public Affairs at Cornell University, New York, and a long-time friend of Gopal and Renchin, put it succinctly when she says that “Gopal gave free rein to his own sentiments in his songs.”

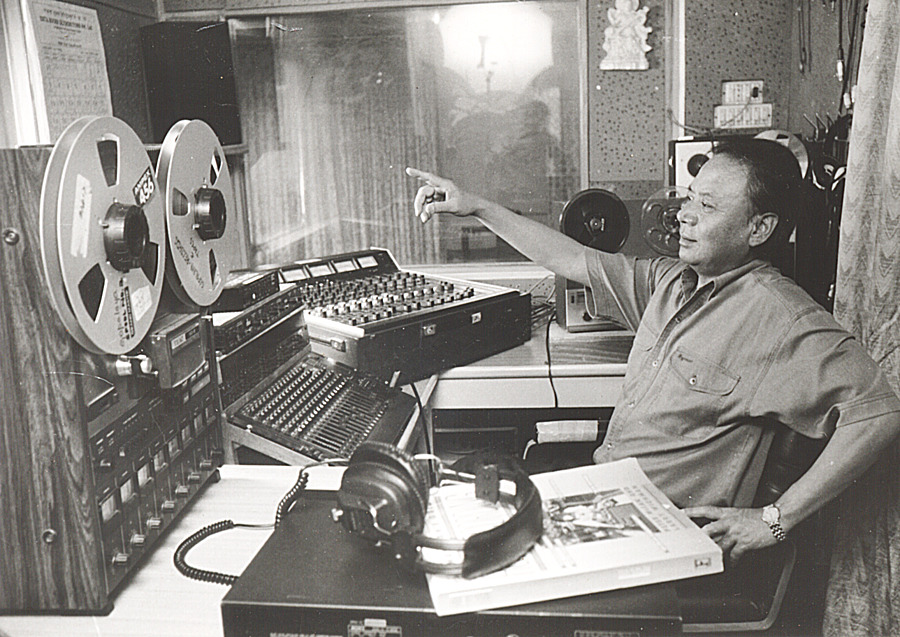

March first met the Yonjans in 1987 when Gopal gave a tour of his recording studio to her and her husband, David Holmberg. “I remember he had racks and racks of spools and tapes. I was familiar with his work especially because of my close association with the Tamang communities in Rasuwa, Nuwakot and other Tamang-dominant areas,” says March. “He made Nepali songs intelligible for them because of his unique and original creations with influences from the Tamang community. His musical poetry was original and new for that time and place.”

In the process that lasted more than 25 years, Renchin has sorted, labelled and categorised documents and tapes, all the while seeking and outlining a long-term storage strategy.

When March reconnected with Renchin in Kathmandu in 2013, an informal query to the latter about her plans for the preservation of Gopal’s work, led to March suggesting archiving his work at Cornell University in Ithaca, New York.

“It was an excellent proposition. I immediately agreed but informed Kathryn that I was still working on the documentation and that it could take me some years to have everything together,” says Renchin. “But then came the 2015 earthquake which exposed Nepal’s vulnerability and inability to provide a safe haven for an artist’s work. Neither the government nor the stakeholders could guarantee the safety of his work. That was when I decided to move all his original work to Cornell University.”

The University of Cornell is one of the few universities in the US which does archive work for artists. Gopal is the first artiste from Nepal to have his work archived at the university. “Gopal Yonjan’s work is the first from Nepal, and in fact, South Asia, to be archived at Cornell University,” said Phulman Bal, writer and general manager of Nepal Television. “I had written and researched extensively on Gopal Yonjan and the ongoing archival work when I was a working journalist.”

Gopal’s creations today sit securely in an archival vault at the university library along with his notebooks, cassettes, photographs, published work, awards and some of his instruments such as his beloved harmonium. The university has archived his work at the ‘Rare and Manuscripts Division’ in the archival vault, a temperature-controlled room, three levels underground.

There are two aspects to archiving Gopal’s work at Cornell University—preservation and restoration, and digitisation. While the initial intervention in terms of preservation is complete, the university is currently working on the restoration work. “Restoration is the hardest and the most time-consuming process because every spool needs to be fumigated and sanitised for the degeneration to stop immediately,” says March. “The library will then move on to the digitisation process, which comes under cataloguing, which when complete will open the world of Gopal’s music and a view of the digitised version of his personal assets to the general public.”

The archive at the university library is accessible to scholars and researchers with the required credentials and a prior appointment with the library. But once the digitisation is complete, the digital archive will be available to all. “Gopal’s work will then be accessible to scholars and everybody else. A Nepali migrant worker in the Middle East wanting to listen to his songs can then just go to the website and listen to his originals,” says March. “Everyone at the university is committed to the idea that Gopal was a significant figure in Nepal and South Asia and has kept archiving his work in high priority.”

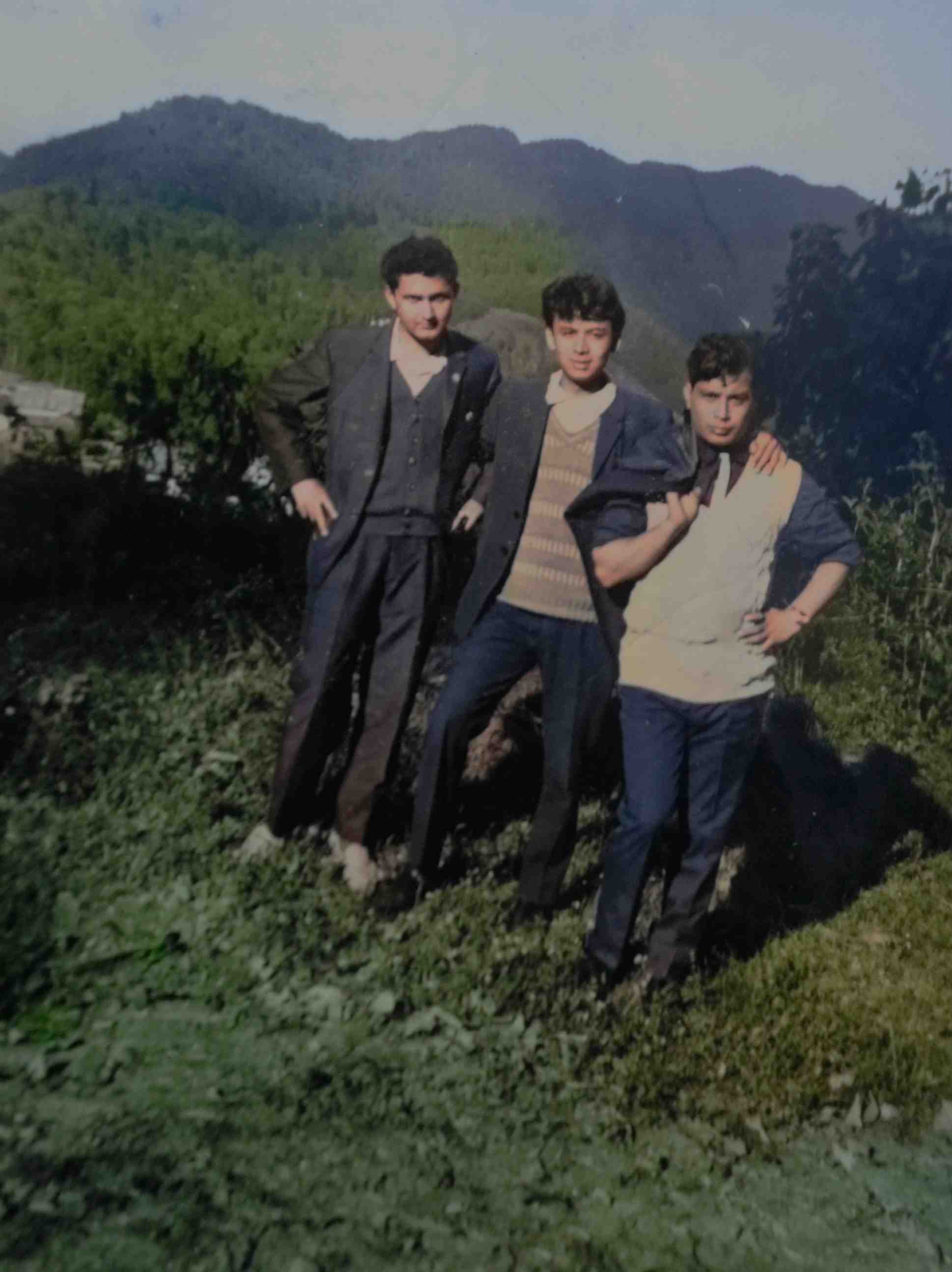

Gopal started his musical career as a flautist. He wrote his first lyrics in 1963 and his first musical composition was recorded in 1964. Gopal was a shaper of public music heritage, as seen with his work with Radio Nepal from 1967 onwards and the Police Club from 1969 onwards, for which he would go on to compose at least 10 songs and pieces annually for 20 years.

Renchin met Gopal when she was 16 in 1968. Fresh off the boat from a convent school in Kalimpong, Renchin remembers her first encounter with her soon-to-be husband. “It was my first day at St Xavier’s school as a teacher. I was walking past the school library when my attention was caught by a boy singing a tune on a harmonium. I stood transfixed,” she says. “That was my first impression of him and it’s a memory imprinted on my mind.”

Since her husband’s death, Renchin has become the keeper of their shared memories and the protector of the memories her husband shared with the world.

She had been filing away her husband’s work, a note here, a song notation there, even when he was alive. “The documentation of Gopal’s work started when he was alive. He would just scribble on a scrap of paper and leave it lying around. I would collect them and keep them safe,” she says.

But the actual work of documentation started after his death. Renchin meticulously searched for his lyrics and composition and started recording them. “He was a composer, so it was important to record his songs. Four months after his passing, I went to Mumbai with my younger son to record nationalistic songs which I had acquired from the Police Club since Nepal did not have the facility nor the technology back then.”

Since then, Renchin has been recording one or two of Gopal’s songs every year.

In 2014, a year after her meet-up with March, Renchin travelled to New York to Cornell University to give a presentation on why Gopal’s work needed to be preserved.

“I interviewed 16 people in Nepal and India on the value of Gopal’s work. It was a 32-hour-long interview that I had to cut to 8 minutes for the presentation. One of the people I interviewed was Chhatra Gurung, who used to work with Gopal at the Police Club,” she says. “I went to Darjeeling to meet some of his contemporaries from Kala Mandir; interviewed Tejendra Gurung, a choreographer who taught Gopal how to dance and perform in a school play and several others.”

In 2016, Renchin started sending archival materials to the university. “The university understood the diversity of Gopal’s work when I told the administrative and academic staff of the university that there are 16 categories and styles of music and compositions. We have an agreement with them that all of the archived work should be made available to any Nepali free of cost,” says Renchin.

Her decision to send Gopal’s materials for archiving to another country was met with furore from certain sections who questioned the purpose behind shipping Gopal’s work to the US citing Gopal as Nepal’s treasure and his work rightfully, Nepal’s. Amid criticism, one of the supporters of Renchin’s decision was Bishwambher Pyakuryal, an economist and former ambassador.

“Cornell University is an accredited institution and the archiving work is not done for monetary gains either by Gopal’s family or the university. His work will be accessible to all free of cost forever,” says Pyakuryal. “Nepalis should understand that given the lack of guarantee by the Nepali government to protect the country’s cultural heritages, it was advisable for Renchin to look for a safe haven for her husband’s work elsewhere.”

As an economist, Pyakuryal underlines the economic benefit Nepal stands to make with Gopal’s work finding a home in a highly reputable institution. Since Gopal is the first Nepali artist whose work has been archived at the university, Gopal has inadvertently put Nepal on the world map of literary cultural revolutions.

“During the dominance of the Beatles in England, the country reported a significant contribution from the music sector to the GDP,” says Pyakuryal. “Nepal should seek a lesson there and start appreciating, preserving and promoting Nepali music, art and literature. In future, once Gopal’s work becomes widely available, there will be interest among the international public to visit Nepal to see for themselves where Gopal came from. The country will then indirectly benefit from it. Now the government must take active steps to do the same for Narayan Gopal, Amber Gurung and other great figures like them.”

The pull of Gopal’s music was not lost on composer and singer Nhyoo Bajracharya, who says Gopal had the Midas touch. Every song of his was a hit, says Bajracharya.

“Gopal’s songs sung by established singers like Narayan Gopal were instant hits, and songs that Gopal wrote for fresh singers were equally successful,” he says. “All his songs are everlasting. I credit him for shaping Nepali music because, until his intervention, Nepalis were heavily influenced by Hindi songs. His creation of songs in almost every genre—nationalistic, spiritual, romance, modern, Western, and dance numbers, among others—opened the door for Nepalis to listen to and enjoy Nepali music. In my opinion, he is the designer of Nepali music and a revolutionary who changed how Nepalis listened to music.”

Besides being one of the greatest composers of his time, Gopal’s contribution as a poet and lyricist is undeniable, says Bajracharya. “I was recording a children’s song in Newa called Chuli Chya Cha Cha and he seemed to have overheard it but I was too shy to approach him. Then in 1990, I recorded a song Na Aau Sapana Bhari for Rasmit Rai. He liked that song and appreciated it. The familiarity between us grew after that. I remember I was invited alongside him to judge a music competition at Bhrikuti Mandap and just sharing the dais with him felt like my biggest achievement,” he says.

Gopal’s wife of 29 years Renchin, who turned 72 this year, says Gopal was never hers alone. “His first love was music and I, his second. But I knew that from the moment I laid my eyes on him, I would have to settle for second place,” she says. “It wasn’t a problem for me because he was meant to share his boundless love with the world through his music and lyrics. He understood that his songs would go on to live forever, beyond his material body. This documentation, curation, preservation and digitisation is a reflection of my love for him and the man he was, and for the younger generation of Nepalis who through his songs and music will understand Nepal’s cultural and literary history.”

Gopal Yonjan’s book of lyrics ‘Gopalaya: Gopalka Geetharu’ will be released today at the event ‘Gopalaya 22’ in Lalitpur.

9.56°C Kathmandu

9.56°C Kathmandu